When you join academia, you join a family. Just like all other families, we have family heirlooms that get tucked away and rediscovered by younger generations. Stories are passed down, old photos are dug up, and memories are shared. Just a couple weeks ago, our lab group reorganized our shipping container that was packed full of old instruments. Tucked away in the back in an old wooden crate, we found some treasures – an old metal main brain and one of the earliest (dare we say world’s first?) nepholometers.

The main brain as it sits today.

Dick Sternberg is my academic grandfather, my adviser’s adviser. He is a leader in the field of coastal sediment dynamics and pioneered studying the ocean with tripods – three legged metal frames that are outfitted with scientific instruments and deployed on the ocean floor. Back in the early 1970’s, his tripod was named R2D2.

Photograph of Dick’s tripod R2D2 (c. 1973) designed for remote operation on the continental shelf.

R2D2 spent many long days out on Washington’s continental shelf recording water temperature, pressure, salinity, turbidity, and even video. This tripod was a creature with a single brain – that central sphere in the photograph above was the main brain. The power supply for all of the instruments was in there; the camera was connected there; all of the data were logged on magnetic tape in there. The nepholometer we found is the big blue instrument strapped to the bottom of R2D2; it used to measure water turbidity.

Nowadays, our instruments are more sophisticated. They are smaller, smarter, and more powerful. Many of them can fit in the palm of your hand. They all have their own power supplies and data loggers. Gone are the days of one creature with a single brain. The tripods we use now are more like a community. Each instrument is self-sufficient, many with more power and memory than the entirety of R2D2. I wonder what students will think of them in a few decades when they are found tucked away in an old storage container for safe keeping.

Tripod deployed on the Eel River Shelf from 1995 – 2000.

Tripod deployed offshore the Elwha River beginning around 2010.

We also found boxes and boxes and boxes of bottom drifters stored in that old container. They were very simple, just bright pink plastic disks. These drifters were designed to track water currents near the seabed. Metal clamps would be added to the drifters until they were neutrally buoyant. After being deployed, the drifters would hover in the water column and drift wherever the current took them. Hours, days, weeks, even years would go by. Eventually, the drifters would wash up on a beach. Hopefully, a curious passerby would see the brightly colored drifter, pick it up, and call in to report their location – many drifters were labelled with contact information and advertised a $0.25 reward. These old drifters pale in comparison to our new instruments with GPS, buoyancy control, and velocity loggers. Still, they hold the title of adventure and suspense.

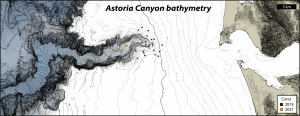

A successful cruise on the R/V Sikuliaq in early April, 2023, has kicked off our year-long experimental program exploring sediment gravity flows on the Cascadia Margin. We placed moorings and bottom boundary layer tripods in the upper canyon reaches of two systems: Astoria and Quinault. These two canyons have very different morphologies and relationships with their modern-day sediment supply, the Columbia River. With the instrumentation we are hoping to capture a range of sediment gravity flows over the year-long deployment. Seabed coring of the canyon thalwegs and surrounding continental shelf and slope give us clues as to triggering mechanisms, gravity-flow dynamics and seabed deposits resulting from these flows. UW Sediment Dynamics group participants: Andrea Ogston, Chief Scientist; Evan Lahr, Tripod Builder and Coring Op Lead; and Sarah Vollero, Coring Ops.

A successful cruise on the R/V Sikuliaq in early April, 2023, has kicked off our year-long experimental program exploring sediment gravity flows on the Cascadia Margin. We placed moorings and bottom boundary layer tripods in the upper canyon reaches of two systems: Astoria and Quinault. These two canyons have very different morphologies and relationships with their modern-day sediment supply, the Columbia River. With the instrumentation we are hoping to capture a range of sediment gravity flows over the year-long deployment. Seabed coring of the canyon thalwegs and surrounding continental shelf and slope give us clues as to triggering mechanisms, gravity-flow dynamics and seabed deposits resulting from these flows. UW Sediment Dynamics group participants: Andrea Ogston, Chief Scientist; Evan Lahr, Tripod Builder and Coring Op Lead; and Sarah Vollero, Coring Ops. The project is being undertaken through a collaboration with the USGS Pacific Coastal and Marine Science Center (led by Dr. Jenna Hill and Kurt Rosenberger). In addition, we had the pleasure of being joined on the cruise by a UW Sediment Dynamics alumni, Dr. Emily Eidam, Oregon State University, and graduate students Adrian Heath (OSU) and Jonathan Moore (V Tech).

The project is being undertaken through a collaboration with the USGS Pacific Coastal and Marine Science Center (led by Dr. Jenna Hill and Kurt Rosenberger). In addition, we had the pleasure of being joined on the cruise by a UW Sediment Dynamics alumni, Dr. Emily Eidam, Oregon State University, and graduate students Adrian Heath (OSU) and Jonathan Moore (V Tech).