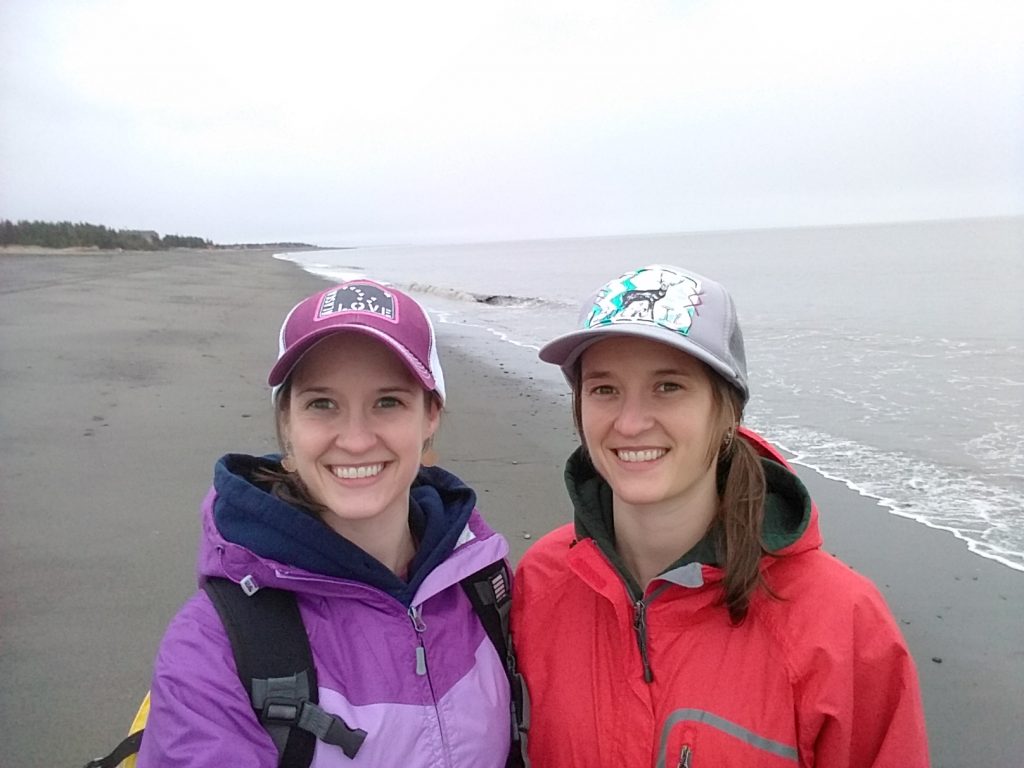

Participant Profile: Amanda and Mallory Millay

by Eric Wagner

In late 2015, thousands of common murres began to wash up along west coast of the U.S. and Canada. The highest concentrations were in southern Alaska, where the species breeds in abundance. Reports of sickened and dying birds came in from the Aleutians, from Juneau, from as far inland as Glennallen. In some places, dead murres lay in neat, unbroken lines among the wrack following a high tide, body after body after body. The wreck would continue into 2016. In the thick of it, the Fairbanks office of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game was taking up to seventy calls per day from concerned citizens. Alaska wildlife officials said the murre die-off was the largest in state history.

It was in the midst of the wreck, during January of 2016, that Amanda and Mallory Millay happened to be walking along a beach near Kenai, Alaska, where they live. The twin sisters saw their share of dead murres that day, and like everyone else they wondered how widespread the problem was. When they read news articles about the wreck, they often saw, in addition to the expected quotes from government scientists, accounts from people who were part of a volunteer group. This group sent people out to different beaches once a month to survey for dead birds, and the data these people collected were proving critical to understanding the scope of the die-off.

“That was what brought us to COASST,” Amanda says. “It seemed like a great program for extensive data gathering.”

Amanda and Mallory decided they would volunteer together. Working as a pair would help motivate them, especially, as Mallory says, “when the weather is gnarly.” And it is often gnarly on the Kenai Peninsula. Their survey beach—Cannery Beach North—can go through great seasonal transformations, from a flat sandy plain in the summer to one covered with snow and ice blocks in the winter. “The beach becomes a totally different landscape once the snow starts to melt,” Mallory says.

Although COASST was the Millays’ first real foray into citizen science—“We did some beach cleanups and things before, but nothing like this,” Mallory says—it was hardly their first exposure to the ocean. They grew up mostly in Ketchikan, and spent a lot of time on the water as kids. Amanda later worked with seabirds in college and completed an internship with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service at St. Lazaria Island, about twenty miles west Sitka. She now works on water quality issues for the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation. Mallory, for her part, majored in geography and environmental science in college, and did some work for Conservation Northwest down in Washington. She now works for the Alaska State Troopers.

Although they were initially drawn to COASST by a murre wreck, the Millays don’t usually find too many dead birds during their surveys. The carcasses they do come across are often gulls—the result of human-seabird interactions. Their beach is near the mouth of the Kenai River, which supports a thriving salmon dipnetting season during the summer. Crowds of people descend on the peninsula, and, as Amanda says, “all the garbage and fish parts draw the gulls in.” Dogs get a few; people run over some in their cars. “At first dealing with the dead birds made me kind of sad, but now not so much,” Mallory says. “You know it’s coming, so you kind of get used to it.”

This, then, is another of Cannery Beach North’s great swings: the empty beach in the winter, the packed beach in the summer. Through it all, the Millays go out and search for birds. “People do all sorts of crazy things on the beaches, so no one pays us any mind,” Amanda says. “Someone might give us a funny look, but no one has stopped yet.” Once, a person thought they were playing Pokemon Go, what with the way they were scrutinizing the sand.

Still, even if they are curios to passing beachgoers, knowing that they are giving the sometimes opaque practice of data collection a bit more of a human face can be its own reward. “I think COASST helps make science less intimidating to the general public, more relatable to people,” Mallory says. “It’s nice to know you’re helping to solve a problem.”

COASST is fortunate to have such hard working,talented observers, as Amanda & Mallory, helping with your important work. They do at times invite others to join them on their survey walks. More eyes, more awareness.