by Eric Wagner

Sakuma Point is an unprepossessing park along Boat Street, near the University of Washington. Not quite half an acre in size, the park is sandwiched by a popular restaurant and canoe rental shop on the left, and a storage warehouse on the right. Visitors can sit at a bench or table overlooking a small stretch of Portage Bay and relax or eat their lunch. Or, if you are Charlie Wright, you count birds for ten minutes.

“I try to make it out here every day,” Charlie says on a bright spring afternoon. He is standing at the water’s edge with a pair of binoculars, calling out species almost the instant he sees or hears them. “There’s a crow,” he says. “Another crow… six lesser scaup over there.” Something behind him chirps. “Song sparrow,” he says without looking back. Another chirp. “White-crowned sparrow.” A few gulls drift in the distance. “Glaucous-wing or hybrids,” he says. “They’re too far away for me to tell.” Ten minutes of this pass, and then he calls time. “Now I upload the list to eBird,” he says, “and that’s the survey.”

Yes, hard as it may be to believe, Charlie—COASST’s stalwart data verifier, he who scrutinizes almost every single photo volunteers send in—likes live birds too. A lot. “I’ve been watching birds in general pretty much since I started having memories,” he says. He was leading birding trips for the Rainier Audubon Society in southern King County by the age of eleven, and has done field work with birds all over the world, from Alaska to Peru. A few years ago, he was part of a team that drove all over Washington, ultimately breaking the state record for greatest number of species seen in a twenty-four-hour period. “Birds are kind of my muse,” he says.

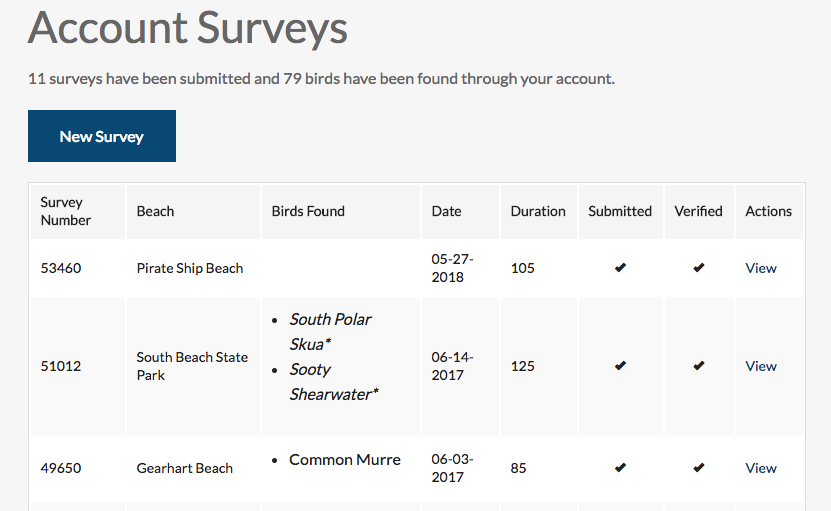

Charlie started as the COASST data verifier in 2010. He performs the vital function of confirming the identity of every dead bird COASSTers find on their surveys. Each fall, he starts to work his way through the backlog of volunteer submissions from the previous year. Most of the time he has no reason to doubt what a volunteer sends in: he cross-references the datasheet with the photos and concurs with the ID. It takes him all of thirty seconds, tops. “It’s rare for me to spend more than five minutes on anything,” he says. “COASST volunteers are pretty amazing at IDs. They know their birds and how to use the COASST field guide.” In fact, COASSTers correctly identify beached birds to species 89% of the time.

But everyone gets stumped once in a while. Last December, a team of COASSTers surveying a beach up near Hobuck, Washington found a bright, iridescent wing. They puzzled over it. Was it a Steller’s jay? They did not think it was, so they sent it in as “unknown.” Charlie spent a few minutes with it before he made the ID. “It was a purple gallinule,” he says. “It was the first time the species was documented in Washington.”

Even with his lifelong interest in birds, IDing a dead bird still is not completely intuitive for Charlie. “With some of the tough ones, you have to take body parts and key them out,” he says. He might use the COASST database of photos—“the largest collection of dead bird photos in the world,” he says—or some of the more technical guides at his disposal. After all, even though COASSTers have found 181 species to date, five or six still show up each year that no one has ever found on a survey before. “Those rarities are always in the back of my mind,” Charlie says. “This body is probably a common murre, but it could be… something else.”

In May, once Charlie has brought the annual backlog of roughly ten thousand photos down to zero, he and his wife head off to Alaska to do field work for the summer, reveling in the realm of living birds, helping monitor their populations and whereabouts. As you read this, they might be in the midst of a point-count survey (a method similar to his hobby activity at Sakuma Point) in the Yukon-Kuskokwim National Wildlife Refuge, camping eighty miles from the nearest town. Or they might be sailing around the Aleutian Islands on a research vessel, helping on a seabird survey. Or they might be even farther north, in the Chukchi Sea. “My COASST work is really complimentary with the Alaska work,” he says. “There’s a seasonality to both of them, ID challenges. It’s just that one is with live birds and the others are dead.”