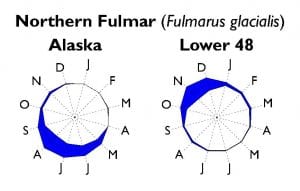

Come late fall into early winter, Northern Fulmars start to appear on Pacific Northwest outer coast beaches. The #2 species in COASST, this denizen of Alaska is virtually absent from the Lower 48 during the spring-summer breeding season. And that’s because they are busy on colonies from Gareloi Island in the Western Aleutian Islands to St. Matthew Island in the northern Bering Sea.

Fully ~1,250,000 are thought to breed in Alaska, mostly on offshore islands with steep cliffs where they scrape out a shallow depression to lay their eggs. The pulse of fulmar on Alaska beaches is actually during the breeding season! But once that season has ended, adults and young-of-the year alike take off for points south.

Well, at least that’s the usual pattern.

In the 2017-18 winter, fulmars were notably absent from Lower 48 beaches. What’s weirder, they suddenly appeared in late winter-spring. In late April, usually the quietest time of year for COASSTers, Jane and Makenzie found 14 Northern Fulmars on their survey of Nye South near Newport in Oregon. Charlie, COASST’s stalwart verifier, noted that across Oregon beaches, not only were there more fulmars than usual, but many of them were light morph birds.

Morph? What’s a morph?

At first glance, fulmars are boring-looking birds. No difference in plumage between adults and immatures, breeders and nonbreeders, or males and females. But the traditional plumage differences in birds just doesn’t tell the story of fulmars.

These birds have two different plumage patterns, which appear to map onto where they breed. So called “dark morph” birds, resembling their Tubenose relatives the shearwaters (but note the stocky, pale bill of the fulmars!), principally breed in southern Alaska. Light morph birds, resembling gulls (but note the telltale plates on their Tubenose bill versus the smooth, featureless bill of the gulls), breed farther north, in the Bering, Chukchi and Arctic. What’s cool about this difference is that COASST can get a sense of where fulmars are coming from based on their plumage.

Most Lower 48 COASSTers find the dark morph. Light morph birds do wash up where they breed during the breeding season, and then migrate down the “other side” of the ocean towards Japan, Taiwan and Korea. But not in 2017-18.

In fact, turns out light morphs have graced Lower 48 beaches in previous years, most notably in 2008 and 2009. Some years – like 2009 and 2018 – have no fulmars during the usual peak, but display a peak in the following spring, whereas other years – like 2006 and 2008 – have a double pulse: once when they’re supposed to arrive, and a second spring peak. Guess which morph arrives in the spring … in both 2008 and 2018, the ratio of light morph fulmars was much higher than usual. Of course the vast majority of fulmars found on Lower 48 beaches are dark morphs, occasionally loads of them, as was the case in 2003/2004.

Since COASST discovered this “light-spring” pattern, we’ve been wondering about it. Who are these guys? And where are they coming from? Given the spring migration timing, it would seem that these birds are actually on the way back north to begin the breeding cycle. So, do light morphs occasionally migrate up the eastern side of the ocean? Or do they always do that, and only sometimes wash ashore? And would that be a weather signal? An ocean circulation signal? A climate signal? Or… We remain mystified!

What’s your prediction as we head into the 2019 fulmar season: dark morphs in winter, or light morphs in spring?