Thank you for visiting the COASST blog. We have recently moved to a new web address:

https://coasst.org/news-views/blog/

See you there!

Thank you for visiting the COASST blog. We have recently moved to a new web address:

https://coasst.org/news-views/blog/

See you there!

In the excitement about the rise of citizen science, the emphasis has tended to be on the science the citizens (meaning an inhabitant of a place) are helping make possible—how they increasingly facilitate important discoveries, how they help professional scientists and decision makers answer questions at larger scales than might have been possible before. Yet these successes hinge on the experience and contributions of the citizens themselves. In turn, projects like COASST are asking: how can citizen science support the best possible experience?

Participation can happen in many ways. In outdoor environmental citizen science programs, it can include interacting with the environment (in COASST, the beach), or the study objects (birds), or scientists, staff members, and other participants (a team and community). The experience of participation is reflected in the effect that participating has on the participants. For example, how does collecting all those important data make a person feel? How might their reasons to be involved change over time? What do they learn or gain from being involved? And, importantly, to what degree would they feel comfortable having the lens of science turned on them?

Using her face for scale, Yurong demonstrates the impressive size of a whale vertebrae at the Port Townsend Marine Science Center.

Helping to explore some of these questions is COASST’s resident social scientist, Yurong He. Her research passion lies at the intersection of humans, the natural environment, and technology. Before joining COASST as a postdoc researcher in 2017, Yurong earned her undergraduate degree in psychology from Beijing Forest University, going on to get a master’s degree in cognitive psychology from the Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. At the same time, she was also a research intern at Microsoft Asia, conducting studies on differing information sharing behaviors among people from China and the United States. “That was when I started to develop an interest in technology,” Yurong says.

Then she came to the U.S. to begin a PhD program at the College of Information Studies at the University of Maryland. It was there she got her first exposure to biodiversity citizen science, combining it with her interest in technology. “My advisor was studying how to use tech to support citizen science,” she says, but as a grad student, she was looking at citizen science from the outside. That changed when she came to COASST. “Here,” she says, “I work from inside the program, so I’m able to take another angle – both are important”.

At COASST, Yurong focuses on the range of lessons that can be extracted from nearly twenty years of surveys for dead birds and, more recently, marine debris. To assess COASST participants’ satisfaction and collect their feedback, her colleagues have sent out questionnaires and interviewed focus groups. Some participants even kept journals for a time, jotting their thoughts and impressions. “All of what the participants have given over and above their beach survey work has been tremendously helpful,” Yurong says. “We want to learn what attracts participants to citizen science in the first place, and what makes them want to stay.”

Through her work, Yurong is gaining insights into how COASST can work better for COASSTers—how it can satisfy their motivations and needs, and empower them to make the difference for the environment. She also identifies themes that can apply to citizen science more broadly. According to SciStarter, there are nearly three thousand formal and informal citizen science programs all over the world, ranging from transcribing old ship’s logs to reconstructing climate (Old Weather), to monitoring water quality, to Project BudBurst, which tracks plant phenology — all projects that might want to know why people initially participate and what keeps them engaged.

“Citizen science is becoming more and more professional and widespread,” says Yurong, who recently attended the third biannual conference of the Citizen Science Association, where she presented some of her findings. “What we learn from COASST goes far beyond our program, and can be applied in a lot of ways.”

Editor’s Note: A closer look at Yurong’s findings will be the subject of the next post!

A little bit more about Yurong. She originally came from China and now lived in Seattle with her husband since 2016. She loves the natural environment, she also enjoys the city life with combination of Asian and Western cultures. In her spare time, she loves to spent time with her family and friends appreciating the beauty of nature, delicious food and coffee. She also loves going to Church and connecting to the local community. She loves listening and singing both contemporary Christian music and classic hymns, and playing drums, like the Cajon to the left, in her church worship team.

Goodbye 2018, you flew right by.

Before 2019 takes loft, let’s pause on the past twelve months in COASST.

Together, we accomplished A LOT!

Beached bird COASSTers completed 3,274 surveys, documenting 2,927 birds comprised of 94 different species. Common Murres are still the top find, making up 30% of birds reported, followed by Northern Fulmars (15.7%) , and Large Immature Gulls (11%).

First-ever records included a Red-footed Booby, Red Crossbill, and Burrowing Owl.

Among the beached birds encountered this year, this Red-footed Booby reported by Mary Sue and Elaine was a first.

Marine debris COASSTers completed 150 small debris, 224 medium debris, and 221 large debris surveys– characterizing 4,395 items!

Water bottles of brand “Nongfu Spring”, like this one found by Roger and John, are emerging as a top marine debris item encountered by COASSTers.

All told, COASSTers spent 5025 hours on the beach doing surveys. Add in travel, paperwork and data entry time, and over 10,000 hours were contributed to COASST. And we heard from many of you that you had fun doing it!

Ron inspired us to wonder: should we amend the COASST Cover Sheet to include participant entanglement?

What did all of those contributions make possible?

Back in the office…

We worked to translate survey data into results, and to share those results with audiences that included COASSTers, scientists, resource managers and the public. A few highlights:

In 2019, marine conditions varied greatly across the range of COASST. In the lower 48, conditions on the beach were more or less back to normal.

In the far north Pacific, Northern Bering and Chukchi Seas, sea surface temperatures continued to be warmer than normal, where we witnessed ongoing unusual mortality of seabird species. To assist with tracking these events, and in collaboration with agencies, communities and organizations throughout Alaska, we launched “Die-off Alert” — a method of reporting observations of die-offs where monthly surveys are not conducted, and a quarterly newsletter In The Wings.

A huge THANK YOU to all of the participants, partners, interns and funders who worked with us this year, and cheers to the year ahead!

In 2013, COASST got its first grant to expand to a whole new data collection protocol – marine debris. Following the tsunami of 2011 that resulted from the Tōhoku earthquake, this was a no brainer. But debris had been on the minds of many COASSTers well before the flotsam from Japan hit our coastlines. In fact, many COASSTers have always gone to the beach armed with a trash bag.

It’s definitely a nuisance, and can also be a health hazard for humans and wildlife alike, but could it also be science?

Could regular monitoring uncover patterns of trash on our beaches?

That’s what Hillary Burgess, the COASST Science Coordinator was brought on to figure out. And after years of development, input from more than 75 pilot testers, 30 interns, marine debris experts and the COASST staff and Advisory Board, we’ve not only got a viable program, we’re starting to “see” the patterns.

This is the first blog in a series revealing what Marine Debris COASSTers are finding. Not quite (!) as numerous as COASST Beached Birds, and certainly not as long in the tooth…, our marine debris program is off to a fantastic start. As of mid-November here are the numbers:

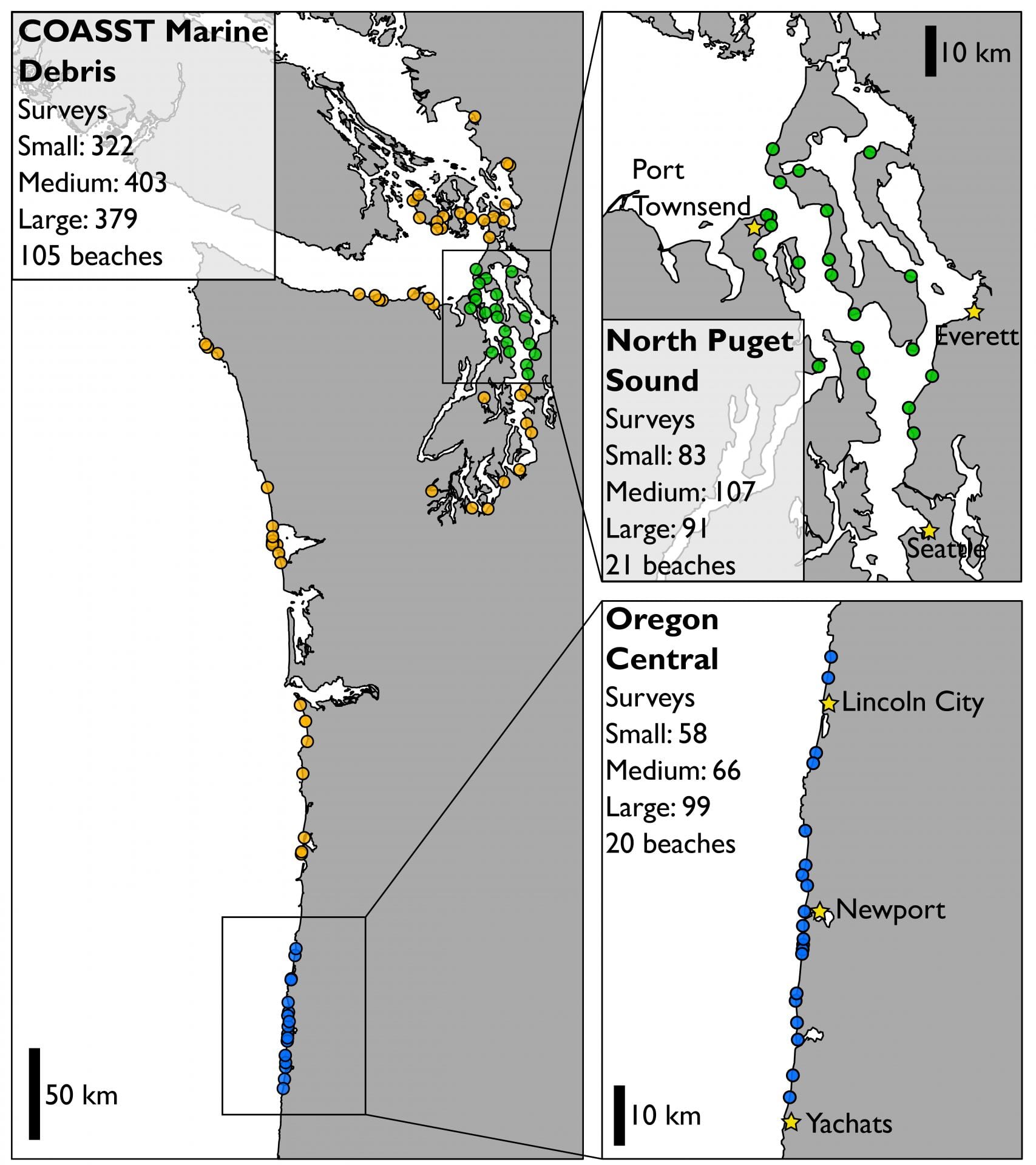

COASST marine debris survey sites have been monitored most consistently for the longest time in North Puget Sound and Central Oregon.

Although COASST marine debris data comes from throughout Washington and Oregon, and even a few test sites in Alaska, we’re confining our analysis for the moment to two regions with a multi-year, multi-beach sample size, and some pretty interesting differences: the outer coast beaches of Central Oregon, and the protected waters of North Puget Sound.

First, let’s step back to some basics. When considering how many beached birds COASSTers find, we use a measure we call “encounter rate” or the number of carcasses a COASSTer might find per kilometer of beach surveyed. Encounter rate treats all beaches – wide ones and narrow ones – the same. And when COASSTers search for carcasses, they comb the entire beach – from the waterline to the vegetation.

Debris is different.

First, we separate debris into size classes:

Second, we report the amount of debris as a function of the area searched. So, not per kilometer, but per 10,000 meters squared (10,000m2), or 100m2 to ensure that the values we present are meaningful. To put these areas into perspective, 10,000m2 is approximately the area of two football fields and 100m2 is one quarter the size of a basketball court.

Third, we take account of the differences in the amount of debris in five (5) different beach zones:

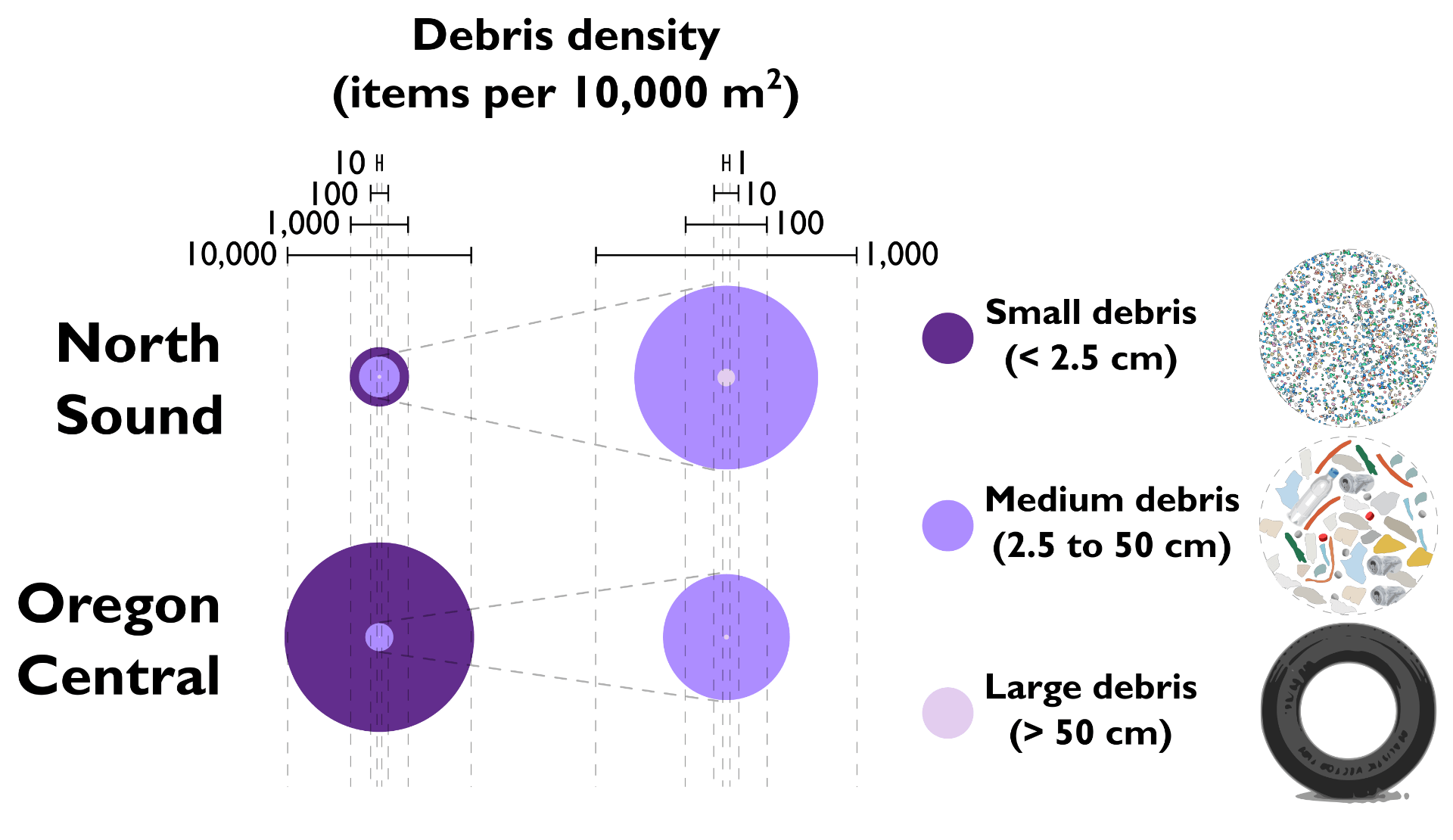

Not surprisingly, small debris – the count of small debris (per 10,000m2) is much higher than that of medium debris, which is more numerous than large debris. And this pattern holds for the outer coast, and for Puget Sound. However, there is a lot more small debris on the outer coast!

The bubbles on the left illustrate debris density, or the estimated count of pieces – by size – you might find on average – from the waterline to the vegetation, scaled to 10,000m2. Small debris (darkest purple) is very abundant, and especially in Central Oregon, where you could find upwards of 10,000 pieces in a 100 meter by 100 meter area of beach! In the middle is a blow-up of the medium and large debris pattern (because those numbers are dwarfed by small debris we had to separate them out and blow them up). To the right is the color code, and a schematic of the relative sizes and types.

And the reverse is true of medium debris – inside waters have a higher density than beaches along the outer coast. The pattern is similar, albeit less pronounced, for large debris.

Where is all of that small debris? Mostly in the wrack, at least in Central Oregon. Conversely, along these outside waters beaches, medium and large debris are primarily found in the vegetation, and secondarily in the wood zone. (Note that small debris are only sampled in the wrack, bare and wood zones).

North Puget Sound COASSTers find similarities, and differences. Small debris is also most numerous in the wrack zone, but the wood zone has just under 90% of that peak density, and the bare zone sports just under half of peak density. Medium and large debris are primarily found in the wood zone, but density in the vegetation falls off quickly, in contrast to the vegetation zone on outer coast beaches.

We’ll compare a kilometer long “typical” beach in North Puget Sound to one along the coast of Central Oregon averaged over the year. You would be lucky to find a single bird in your North Puget Sound beach survey, but you’d likely find 5-10 large pieces of debris, 1,000 medium pieces, and a whopping 2,500 small pieces.

Seems like a lot, until you travel to the coast of Oregon. Here you would find on 3-5 birds averaged over the year, 3-4 large pieces of debris, 2,500 medium pieces, and a stupendous 100,000 pieces of small debris.

The humongous medium and especially small debris numbers are why COASST subsamples the beach. Otherwise, Sisyphus would long since have been successful in rolling his rock up the hill before any outercoast COASSTer finished picking up all of the small debris! A somber note, of course, is that this is what we face along our beaches and in our ocean, and – you guessed it – it’s almost all plastic, with 70% of medium debris and 87% of small debris items being plastic.

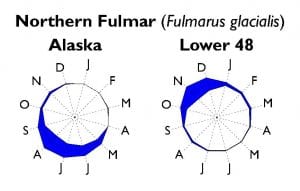

Come late fall into early winter, Northern Fulmars start to appear on Pacific Northwest outer coast beaches. The #2 species in COASST, this denizen of Alaska is virtually absent from the Lower 48 during the spring-summer breeding season. And that’s because they are busy on colonies from Gareloi Island in the Western Aleutian Islands to St. Matthew Island in the northern Bering Sea.

Fully ~1,250,000 are thought to breed in Alaska, mostly on offshore islands with steep cliffs where they scrape out a shallow depression to lay their eggs. The pulse of fulmar on Alaska beaches is actually during the breeding season! But once that season has ended, adults and young-of-the year alike take off for points south.

Well, at least that’s the usual pattern.

In the 2017-18 winter, fulmars were notably absent from Lower 48 beaches. What’s weirder, they suddenly appeared in late winter-spring. In late April, usually the quietest time of year for COASSTers, Jane and Makenzie found 14 Northern Fulmars on their survey of Nye South near Newport in Oregon. Charlie, COASST’s stalwart verifier, noted that across Oregon beaches, not only were there more fulmars than usual, but many of them were light morph birds.

Morph? What’s a morph?

At first glance, fulmars are boring-looking birds. No difference in plumage between adults and immatures, breeders and nonbreeders, or males and females. But the traditional plumage differences in birds just doesn’t tell the story of fulmars.

These birds have two different plumage patterns, which appear to map onto where they breed. So called “dark morph” birds, resembling their Tubenose relatives the shearwaters (but note the stocky, pale bill of the fulmars!), principally breed in southern Alaska. Light morph birds, resembling gulls (but note the telltale plates on their Tubenose bill versus the smooth, featureless bill of the gulls), breed farther north, in the Bering, Chukchi and Arctic. What’s cool about this difference is that COASST can get a sense of where fulmars are coming from based on their plumage.

Most Lower 48 COASSTers find the dark morph. Light morph birds do wash up where they breed during the breeding season, and then migrate down the “other side” of the ocean towards Japan, Taiwan and Korea. But not in 2017-18.

In fact, turns out light morphs have graced Lower 48 beaches in previous years, most notably in 2008 and 2009. Some years – like 2009 and 2018 – have no fulmars during the usual peak, but display a peak in the following spring, whereas other years – like 2006 and 2008 – have a double pulse: once when they’re supposed to arrive, and a second spring peak. Guess which morph arrives in the spring … in both 2008 and 2018, the ratio of light morph fulmars was much higher than usual. Of course the vast majority of fulmars found on Lower 48 beaches are dark morphs, occasionally loads of them, as was the case in 2003/2004.

Since COASST discovered this “light-spring” pattern, we’ve been wondering about it. Who are these guys? And where are they coming from? Given the spring migration timing, it would seem that these birds are actually on the way back north to begin the breeding cycle. So, do light morphs occasionally migrate up the eastern side of the ocean? Or do they always do that, and only sometimes wash ashore? And would that be a weather signal? An ocean circulation signal? A climate signal? Or… We remain mystified!

What’s your prediction as we head into the 2019 fulmar season: dark morphs in winter, or light morphs in spring?

Exxon Valdez, Deepwater Horizon – these oil spill disasters have been devastating for marine wildlife, especially seabirds and marine waterfowl. Once oiled, the body feathers of a seabird lay slick against the skin, losing the insulating properties that keep birds warm and dry. At the same time, the added weight of the oil often prevents the bird from taking off. And the toxins birds ingest while attempting to preen? Well, suffice to say that oil and seabirds don’t mix.

Oiled secondary feathers of a Black-legged Kittiwake found on Griffiths Priday State Park (WA) in early 2018

And even a little bit of floating oil can be deadly. One gallon of oil can contaminate hundreds of gallons of water. Floating oil can be carried hundreds of miles from the spill site. Oil leaking from the Exxon Valdez tanker in Prince William Sound was swept by currents southwest out of the Sound along the Kenai Peninsula past the entrance of Cook Inlet to the Alaska Peninsula, almost 500 miles away from the spill site.

On Tuesday (14 August), a 700 gallon spill of diesel fuel was reported in Yaquina Bay, in the marina housing the fishing fleet. Stories in the Oregon news show aerial shots of the sheen from the spill, complete with a flock of gulls. While the oil seems to have been largely contained, will there be oiled birds? COASSTers from Newport and environs got out on their beaches immediately to record a baseline survey. At this time of year, murres, cormorants and gulls nesting at nearby Yaquina Head are ready to fledge their chicks. The Coast Guard – acting quickly – helped boom the area, preventing the oil from spreading in the Bay and getting out into the ocean. But that doesn’t prevent birds from flying into the Bay.

The vast majority of COASST surveys are oil-free, no oil on the birds or on the beach. In fact, COASSTers find most evidence of oil impacts from chronic sources – small bits of oil on birds unconnected to a reported oil spill. Extremely rarely, COASSTers come upon an oil spill. Quick reporting to the local authorities can save the day. In the case of the Yaquina spill, we’re standing by waiting to hear from local COASSTers whether anything untoward washes in to nearby ocean beaches.

As of this posting, no oil or oiled birds have washed up on beaches near Yaquina Bay.

A dried squid arm? A plastic who-knows-what? A monster? COASSTer Maddie Rose sent in this intriguing photo from Rialto Beach, WA with a “got a clue?” question.

COASSTer Maddie Rose sent in this intriguing photo from Rialto Beach, WA with a “got a clue?” question.

We were on it! University of Washington Fish Curator Luke Tornabene took only a minute or two before returning this intriguing answer:

“Based on spines and dorsal fins towards the end of the tail, it’s some sort of skate, probably genus Raja or Bathyraja. People used to make deranged looking dolls from dead, dried out skates like this, contorting them to look like alien-like demons. They called them Jenny Hanivers.”

The long, spiny appendage in this photo is actually the tail. What looks like a skull with an elongated beak is the body and shriveled nose, or more properly rostrum, of the skate; probably a long-nosed skate according to Fish Collections Manager Katherine Maslenikov. The wings of this fish are long gone.

Skates are slow-growing, bottom-dwelling fish that make their living “flying” just above the sandy substrate, occasionally digging in to “pounce” on a buried shrimp, crab or small fish. In a twist of fate, the egg cases of these fish are known as a mermaids purse.

But,… what?!? Jenny Hanivers??

Turns out one of the weirder ways skates and rays have been used by people is as curiosities. These cartilaginous fish, related to sharks, were flipped over and “shaped” into gruesome likenesses of imagined sea devils or maybe evil-looking mermaids. After being dried out and shellacked they were sold in port cities and seaside towns as far back as the 16th century. The origins of the name are obscure, but some articles reference jeune fille d’Anvers which translates as girl from Antwerp.

Intentionally fishing and drying out sea creatures as tourist trinkets, whether sea stars, sea horses or Jenny Hanivers, has fortunately fallen out of fashion. But beach combing is still a great way to come upon all sorts of interesting bits and pieces brought in on the tide and tossed ashore by a wave to dry in the sun.

Keep ’em coming!

The Coastal Observation and Seabird Survey Team (COASST), a citizen science program based at the University of Washington’s School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, is recruiting undergraduate interns for the upcoming academic quarter.

COASST interns work as a team directly with staff and gain valuable, hands-on experience with citizen science programs and the complexities of volunteer-collected data.

Internship tasks may include:

Interested students should send an email to:

Jackie Lindsey (Participant Coordinator) at coasst@uw.edu

by Eric Wagner (who has a new book out: “Penguins in the Desert“)

In addition to writing for COASST from time to time I’m also a volunteer, which means I went to a training, which means that, midway through said training, I watched Hillary Burgess, COASST’s Science Coordinator and the trainer for the day, pull out a big plastic bin full of bird specimens for all of us to practice measuring and identifying. And as I was measuring the chords of variably patterned wings, or examining the webbing between the toes of a foot, I found myself wondering: Where exactly did they come from?

It was to get an answer to this question that I found myself not long ago in a basement lab of the UW Fisheries Science Building in Seattle with Hillary and Jackie Lindsey, COASST’s Volunteer Coordinator. When not in a plastic tub or suitcase, the bird teaching collection resides in two large freezers—a miniature natural history museum dedicated to the practice of using COASST’s field guide, Beached Birds. Inside the freezers are scads of small tubs, all of which are have labels with names like “COMU feet,” “Waterfowl: Diving Duck Feet,” and “Pouchbill feet,” among others. (There is also one called, memorably, “Heads” – remember bill measurement practice?)

As any COASST volunteer knows, the teaching collection is central to their training. But teaching birds get handled and measured, frozen and thawed and frozen again on a regular basis, so their shelf life can be limited. Fresh specimens are needed at a fairly steady rate, and the collection needs to include the range of shapes, sizes and patterns encountered in Beached Birds. But COASST can’t simply repurpose carcasses that COASSTers find on their surveys. Permits are required from the relevant state and federal agencies. So are non-food freezers to keep specimens sufficiently cold. When certain species are scarce, COASSTers have occasionally been added to permits so that they can take on this above-and-beyond task, but COASST also has a network of contacts to whom they reach out. Happenstance rules the day—they can’t just ask the birds to fall out of the sky, Jackie points out—so mostly what comes back are Alcids and large immature gulls. That doesn’t mean there isn’t a wish list of a sort. “We’d really like a Pigeon Guillemot wing,” Jackie says, “but those are surprisingly hard to come by.” A useable specimen must be collected fresh and intact, after all, as if it did just fall out of the sky.

On this day, Hillary and Jackie are preparing several Common Murres that had washed up on the beaches of Seattle’s Discovery Park the previous October. With great precision, Hillary and Jackie remove the relevant parts: the wings at the shoulder, the feet just above the ankle joint so the tarsus can be accurately measured. The next step was adapted from processes used to prepare specimens at the Burke Museum of Natural History, a museum on the University of Washington campus that maintains the largest spread wing collection in the world. In fact, Ornithology Collections Manager Rob Faucett has mentored COASST staff and students in the practice of identification, preparation and care of specimens over the years. Hillary and Jackie take the wings and feet to a “setting station” (a large, flat piece of Styrofoam) and carefully position the specimens so that the tarsus and wing chord can be measured, and all the characteristics used in identification can be easily viewed–like number and shape of toes, and any pattern in the secondaries. The specimens will remain here for a few days to fix into these positions, before being labeled according to species and added to the appropriate Foot Type Family or upperwing pattern bins in the freezer.

In addition to the murres, there are a few other specimens already laid out: a pair of Black-legged Kittiwake wings and feet collected by Hillary and her father while on a COASST training trip to the Long Beach Peninsula of Washington, a couple of Rhinoceros Auklets (Alcids) from the recent die-off off the Washington COASST, and two cormorant feet, one with a thick yellow band on it and the sequence JH8. The band catches my eye. I ask Hillary if she knows anything about it, if there was any information on the bird to which it belonged. “Whenever a banded bird comes to COASST (as a specimen or is reported on a datasheet) we enter the relevant information into the North American Bird Banding Laboratory database maintained by the USGS. If the researcher who banded the bird has entered the original banding data, it is shared with COASST and we wind up with a window into that bird’s life—I’ll check our records.”

A day later Hillary sends me an email. The bird had been found deceased on a beach in Whatcom County, Washington in 2017, but had been banded four years earlier—in the spring of 2013 on the Oregon coast, Clatsop County. The bird was at least six years old. And now, almost dry, it’s feet were ready to take their place in a bin on a shelf in the freezer, to become objects of a different COASST fascination: examples of feet with four webbed toes.

What do the following things have in common?

They are all uses of COASST data — and the list goes on!

Data are summarized and appear in outlets that range from reports, to peer reviewed publications, to media articles.

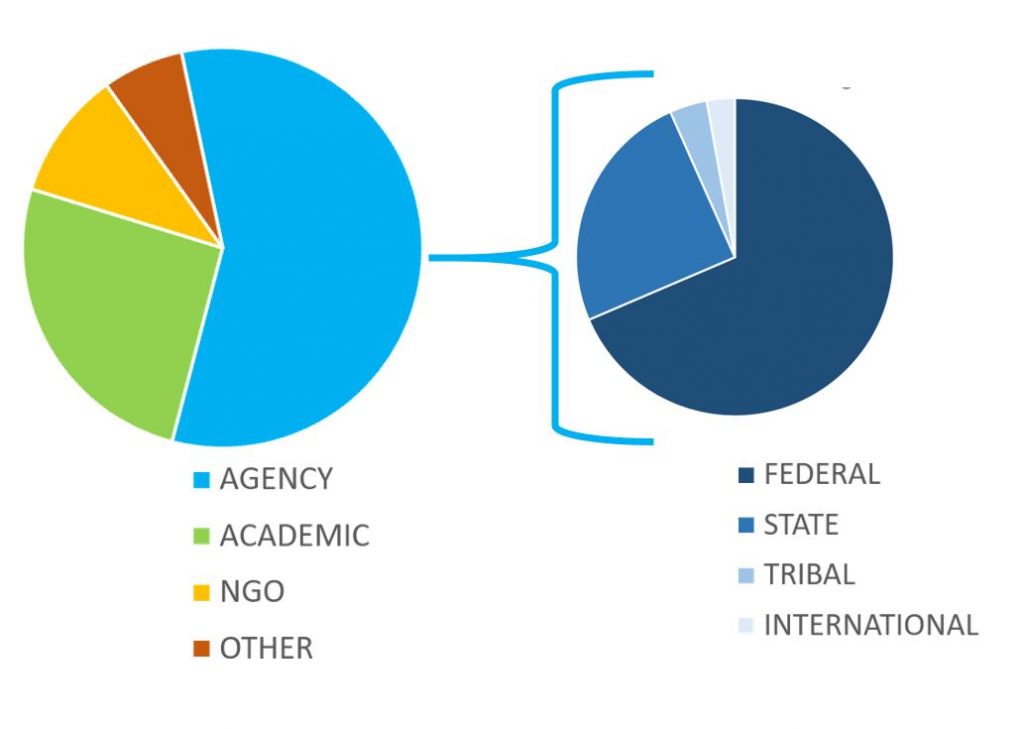

From 2008 (when we started keeping track) to today (Feb 26 2018), 207 requests for COASST data have come to the office. Most requests come from partners at resource management agencies like the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, United States Fish and Wildlife Service, National Park Service, and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, but we also hear from academic researchers, non-profit organizations and the media.

Most of the 207 requests for COASST data have come from government agencies. Of those, the majority are federal partners.

Although the beached bird program was designed to generate a baseline against which the impact of catastrophic events, such as oil spills, could be measured, there have been myriad other uses of the high quality information that COASSTers collect!

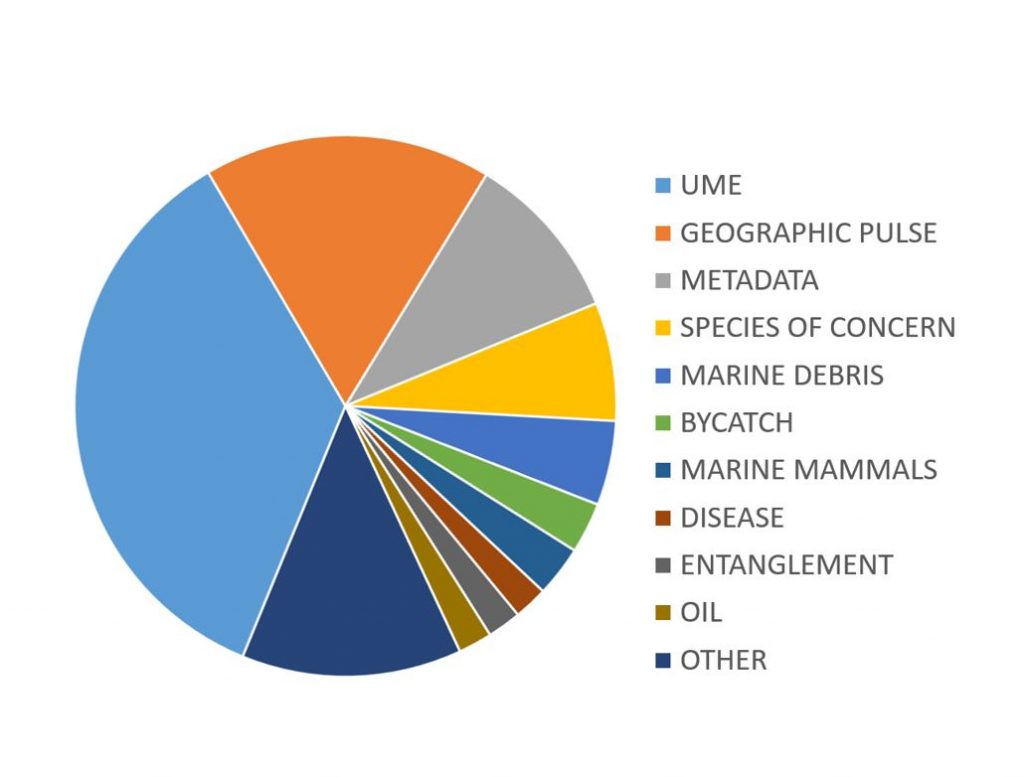

Of course, the most common use of our data is in defining, tracking, and explaining deviations from the “normal” pattern of beached birds at specific times and places. With a serious uptick in frequency and magnitude since 2014, die-offs are keeping all of COASST busy!

Information about UMEs (Unusual Mortality Events) is in high demand. Requests for recent local information are also popular, “what’s been happening in my area lately?”

So how are COASST data used in “real time”?

During an unusual mortality event, COASST keeps the pulse coming in from surveys and anecdotal reports, and provides regular updates to the agencies with jurisdiction over the affected species and locations. These agencies make decisions about things like whether to collect carcasses for necropsy, closure of public lands, and hunting/harvesting of seabirds and their eggs.

Collectively, we pull together the puzzle pieces as they unfold: Where, when, who and how many birds? Do we know why they died? What precautions should be taken? Are there other unusual things happening in the ecosystem at the same time?

We attempt to answer these questions, and collaboratively craft the fact sheets that wind up on our respective websites.

COASST surveys are a valued and varied source of information. If you find yourself wanting to know more about how COASST data are used, be sure to check out COASST Stories.

A note to our intrepid marine debris participants: it takes some time to gather enough data to detect patterns and uncover stories. Because this program is so new, we’re just starting to be able to do these things, and plan to feature what we find very soon!