Of the many things we save for last – doing the laundry, getting milk on the way home, packing a toothbrush – COASST’s human/dog and vehicle data is the same: last, but important.

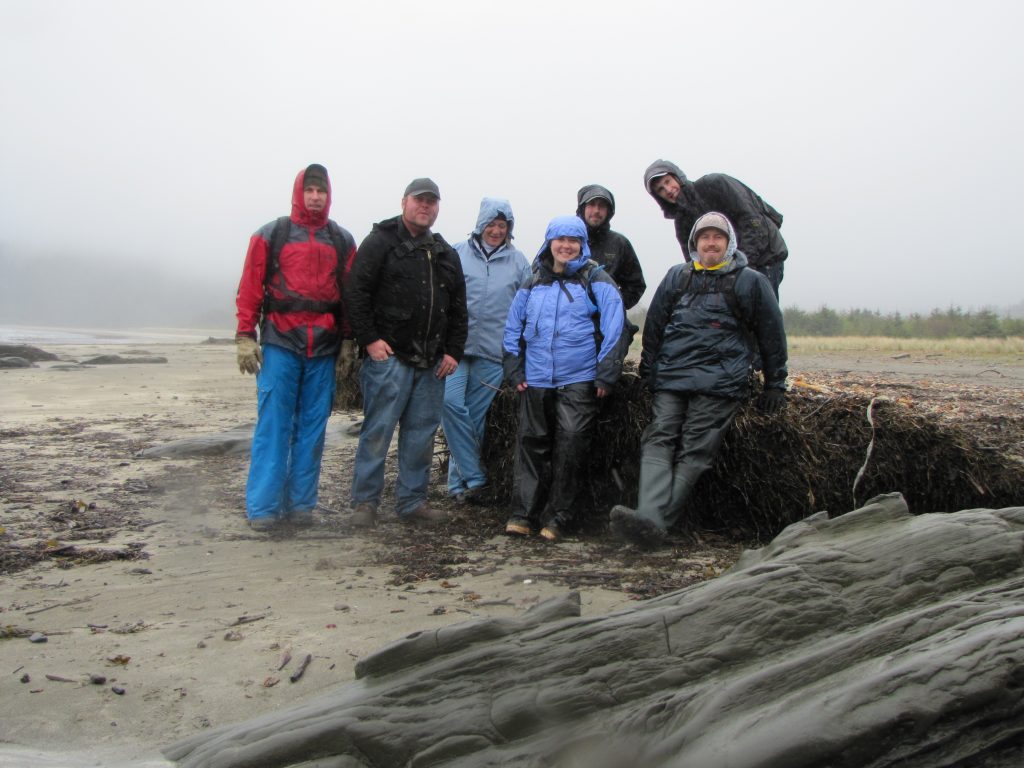

Wide or narrow beaches, human/dog and vehicle counts are saved for last. Why? In some areas, human presence truly crowds the beaches – anyone who has visited the Oregon coast in July knows just how crazy it can get. In order not to double count, humans, dogs and vehicles are counted only on the return leg from the turnaround point back to the start.

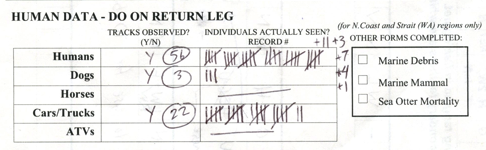

—> Helpful hints: count humans, dogs and vehicles as you pass, use a tally system for large numbers.

In COASST, definitions count! There’s a definition of what counts as a “bird” and what counts as the “beach.” Not surprisingly, humans, dogs and vehicles have definitions too, to make sure we’re all counting the same things in the same way.

Humans: Homo sapiens, feet touching beach

- Babes in arms? – no

- People in vehicles? – no, didn’t your mom tell you not to look in peoples’ windows?

- People riding horses? – no

- Yourself or your tracks? – no

COASSTers Amy, Gary, and Lauren don’t count their dog Enzo or his tracks since his part of their team.

Dogs: domesticated canines, leashed or not, paws touching beach

- Foxes or coyotes? – no, not a pet

- Cougars? – no (also, that’s a cat)

- Toy dogs in purses? – no, paws must touch the beach

- Your own dog or its tracks? – no

Cars/Trucks: fuel-powered engine, 4 wheels, total weight approx. 1,815kgs (5,000lbs), on beach (not in parking lot, for instance).

- Over beach on ferry ramp? – no

- In parking lot above dunes? – no

- On the boat launch? – yes, if the launch is part of your beach

ATVs: fuel-powered engine, 2-4 wheels, total weight approx. 180kg (500lbs), on beach (not in dunes, for instance)

- In the dunes? – no, not part of the COASST beach

- Motorbikes? – yes, count as ATVs

- Bikes? – no, pedal power!

Horses: domesticated ungulate, hooves touching beach

- Sheep, goats or llama? – no

- Deer, elk, or moose? – no

- Rocking horse? – no, but this could count as marine debris

Since its inception COASST has documented 241,542 humans, 43,389 dogs, and 21,797 vehicles: one of the richest sources of local-to-regional estimates of beach use in all seasons. COASST data tell us about beach use that day (tracks=y) and how many people are out (human/dog/vehicle count) during the survey. They also let us evaluate how the carcass deposition index may change as a function of human visitation.

So great work, COASSTers!