Hope everyone is enjoying the first weeks of summer. As usual, the COASST office is bustling with activity – we have new summer interns, we’re getting ready for three beached bird trainings in July, the marine debris program development is progressing, and we’re now collecting data on sea stars (see below)! Just a heads up for those of you along the California, Oregon, and Washington coast, Brown Pelicans are headed north earlier this year. In some years, we’ve seen big spikes of murre chicks around coastal colonies due to Pelican disturbance – be prepared, especially if you survey between Newport and Otter Crest in Oregon North.

Let’s take a look at what’s washed in!

Wing chord = 41mm

Wing chord = 41mm

Ack! Just a wing! But no fear here: if you have the wing key, turn there (that’s what Janet and Carol did), or turn to the wing table!

Alaska wing key: Pale, but not white, so select gray (go to Q25). And hey! There’s not much else going on here: no mottled stripe, no dark primary or secondary tips, no bicolored primaries, and the primary tips aren’t white, they’re still gray. Look close – can you see the tiny white “fingernail”? This has to be a Glaucous-winged Gull (LA6-7).

West Coast wing key: Gray mantle, some species with dark tips and/or dark stripes (looking pretty plain here, but still, go to Q10). If upperwing gray, do wingtips contrast? Nope, not that we can see. Check out the longest primary – at least one white fingernail there, so we’re left with Glaucous-winged Gull (LA7-8).

Wing table: With our wing chord, we’ll zero in on the “Extra Large” row. Upperwing isn’t dark (those near black hues), it’s gray – turn the page or scan across. Simply gray or gray with white linings or gray with black tips? Well, we can eliminate black tips. We’re left with Heermann’s Gull (LA21-22) or Glaucous-winged Gull (LA7-8). Our wing chord is too large for Heermann’s – Glaucous-winged Gull, final answer.

Bill: 44mm, Wing: 20cm, Tarsus: 41mm

Bill: 44mm, Wing: 20cm, Tarsus: 41mm

Sure, this didn’t JUST come in, but we pulled this one to show Chris’ detective work started with FINDING the bird, even before the ID. A fine example of a bird hidden (not even buried!) in wrack.

All regions: Foot – let’s start there. Three webbed toes and no tiny “minute” toe behind – Albatross or Alcids, but the foot is WAY too small for an albie. Flip to Alcids, AL1. Bill is dark, smooth and featureless – murres or guillemots. No white upperwing patch – not a guillemot and bill is too big for a Thick-billed Murre (a rarer-than-rare option in Puget Sound, but still). Congrats – COMU (AK: AL3-4 West Coast: AL2-3).

Wing chord = 26.5 cm

Wing chord = 26.5 cm

Ginger figured this out! Flip back to the wing key or wing table.

Alaska wing key: Secondaries darker than mantle, so select dark speculum (go to Q17). No patches here (go to Q24). There it is: buffy stripe above and white below speculum. The wing chord is larger than 19cm, so we have a Northern Pintail (rare, not in the AK COASST guide).

West Coast wing key: Dark secondaries, go to Q18. Tan stripe above and white stripe below speculum. Definitely larger than a Green-winged Teal – good work – Northern Pintail (WF9-10)!

Wing table: Smack in the middle of “Med-Lg,” and we’ll scroll across to patch/speculum. We have few to consider! NOPI (WF9-10), MALL (WF11-12), WWSC (WF 3-4), KIEI-m (WF21-22). Let’s start from the bottom and work our way up! KIEI male – white underwing – ours is mostly gray. All white secondaries, a la WWSC? Nope. Mallard has a purple/blue speculum bordered by white – not quite. Only one has a “greenish brown” speculum – that’s the Northern Pintail (WF9-10).

Bill: 74mm, Wing: 30cm, Tarsus: 69mm

Melissa notes, “dark brown, belly tan mottling.” Let’s go back to the foot key.

All regions: Webbed foot (go to Q2), fully webbed (go to Q3), 4 toes, all webbed, Pouchbills (PB1). On PB1 we note: NOT a Pelican (wing chord less than 35cm). In Alaska, we can get straight there: tan (or at least not dark) chin. West Coast COASSTers, follow through to pages PB2, PB4, and PB6 to check the measurements of all three cormorants. A bill of 74mm is too big for a Pelagic or Double-crested Cormorant – this is a Brandt’s Cormorant (AK: rare, West Coast: PB2-3).

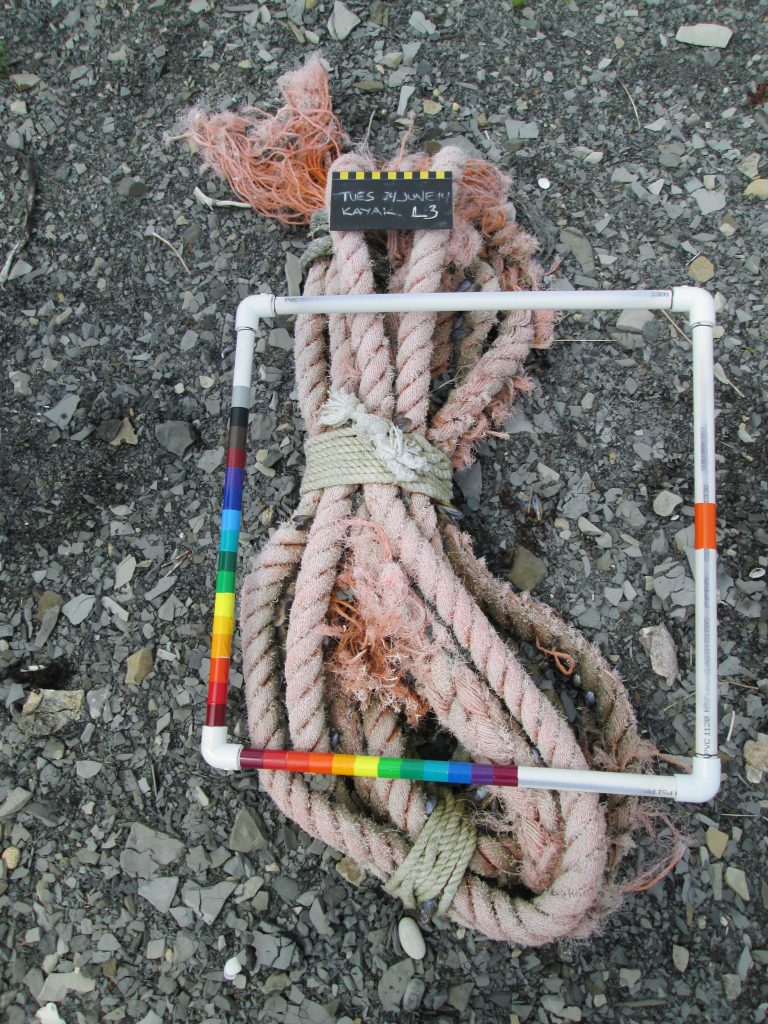

Here’s a buoy that the marine debris team found recently. If you take a close look, you can see the curved pecks from bird bites. Pilot surveys conducted by Marine Debris interns seem to be showing a pattern that’s consistent with research conducted by Gerhard Cadee in the Netherlands. In Cadee’s research, he found bird bite marks on 80% of the foam marine debris he tested! The COASST Marine Debris module will help us understand the degree that birds interact with debris objects.

Here’s a buoy that the marine debris team found recently. If you take a close look, you can see the curved pecks from bird bites. Pilot surveys conducted by Marine Debris interns seem to be showing a pattern that’s consistent with research conducted by Gerhard Cadee in the Netherlands. In Cadee’s research, he found bird bite marks on 80% of the foam marine debris he tested! The COASST Marine Debris module will help us understand the degree that birds interact with debris objects.

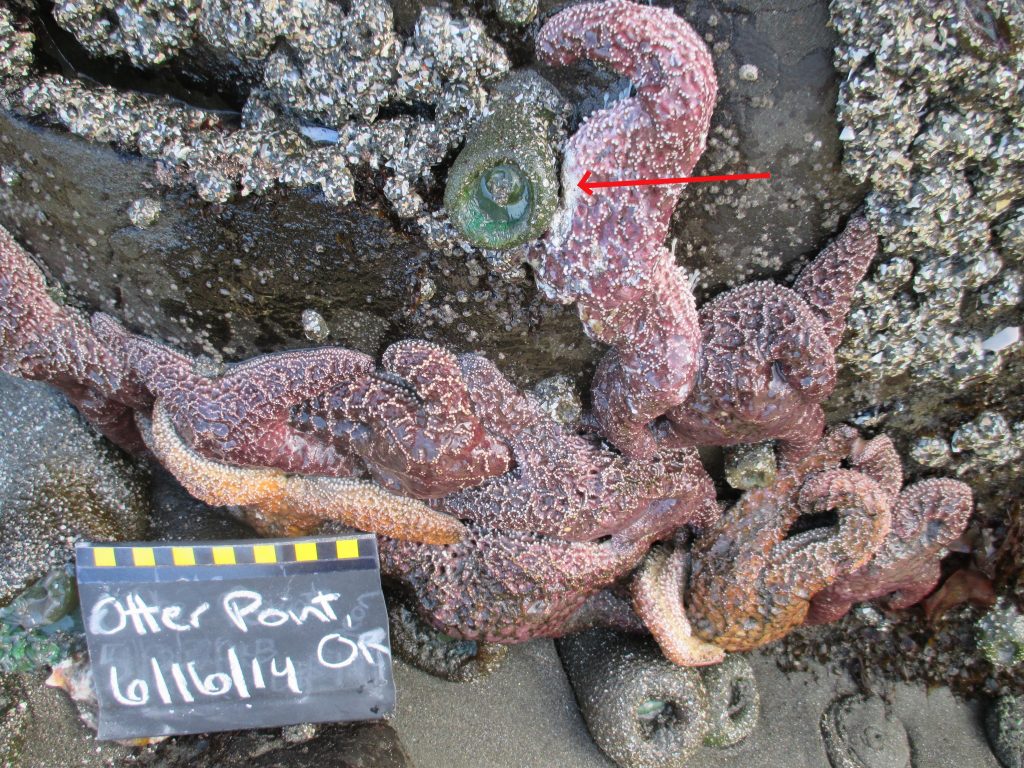

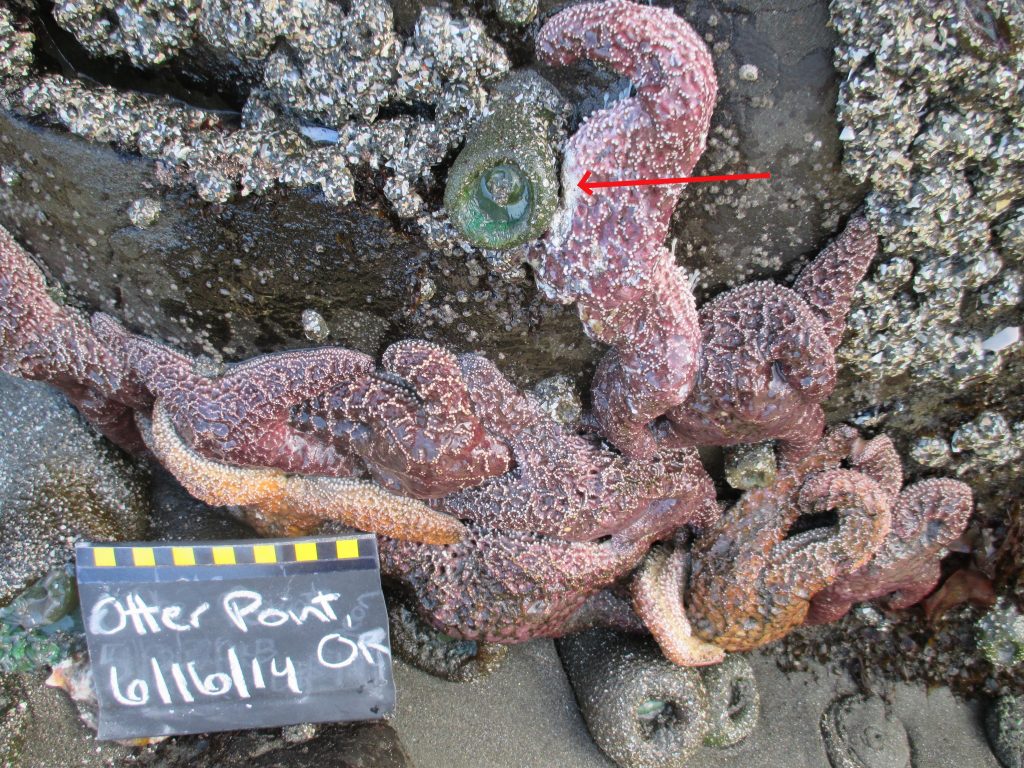

A big THANK YOU to all of you who are helping to collect sea star data. Here’s a photo sent in by Candace, showing sea star wasting disease in ochre sea stars. Sea star wasting disease is currently impacting upwards of 18 species of sea stars throughout the Pacific Coast.

A big THANK YOU to all of you who are helping to collect sea star data. Here’s a photo sent in by Candace, showing sea star wasting disease in ochre sea stars. Sea star wasting disease is currently impacting upwards of 18 species of sea stars throughout the Pacific Coast.

COASST is working with Professor Drew Harvell at Cornell University to document sea star wasting disease using a simple protocol. If you live near a coastal area with cobble, rocky bench, or tide pool coastal sites, we’d love your help with this important, time sensitive project. The protocol and data sheet can both be found on the COASST website in the volunteer toolbox.

Bill: 54 mm, Wing: 44 cm, Tarsus: 67 mm

Bill: 54 mm, Wing: 44 cm, Tarsus: 67 mm Bill: 50 mm

Bill: 50 mm