Hope that all of you are staying warm on your beaches this month! This past weekend, COASST staff conducted trainings in Washington and Oregon, catching up with many current COASSTers and adding some new COASSTers to the team. It was great to see some of you in Long Beach (WA), Charleston (OR), and Port Orford (OR)!

It’s hard to believe that November is more than halfway over. As you get ready for your next survey, take a quick look at your supply kit and let us know if you need any additional cable ties, chalk, datasheets, etc. We’d be happy to send more your way. Also, if you have any completed datasheets sitting around, please send them our way! We can’t wait to see them.

Let’s take a look at What’s Washed In:

Buldir Island – B (AK) 6/27/14 found by Alaska Maritime NWR staff

Bill: 14 mm

Wing: 14 cm

Tarsus: 27 mm

Dark underwing, dark heel, orange bill. Let’s check out our options using the wing key.

Alaska wing key (page 44):

You’ll have to trust us on the upperwing, but…

Choose dark (go to Q2), simply dark (go to Q5), underwing linings not white (go to Q9), wing chord less than 35cm (go to Q10), none (go to Q11), wing chord less than 16cm (go to Q12), underwing simply dark. We’re left with:

Marbled Murrelet-MAMU (AL17)

Crested Auklet-CRAU (AL25)

Parakeet Auklet-PAAU (AL23)

The tarsus of this mystery bird is too long for MAMU’s Alaska range (16-21mm). Flipping to the Crested Auklet, measurements fit, but plumage is mostly dark. Not in the similar species section – Parakeet Auklet has a white breast, belly and undertail (all dark plumage for the Crested). See that white bit of fluff between the two wings? Bingo – Parakeet Auklet.

West Coast wing key (page 33):

You’ll have to trust us on the upperwing, but…

Choose dark (go to 2), choose upperwing simply dark (go to Q3), underwing gray-to-dark (go to Q6), underwing simply dark (go to Q7), wing chord less than 17cm (go to Q8), and select underwing simply dark. We’re left with:

Marbled Murrelet-MAMU (AL14)

Parakeet Auklet-PAAU (AL18).

The tarsus of this mystery bird is too long for MAMU’s range West Coast (14-18mm), so Parakeet Auklet it is!

West Coast wing table (page 32)

You’ll have to trust us on the upperwing, but…

Choose row = tiny (wing chord less than 18cm) and column “dark upperwing” – no pale underwing linings. We’re left with:

Marbled Murrelet (AL14)

Leach’s Storm Petrel (TN11)

Fork-tailed Storm Petrel (TN9)

Parakeet Auklet (AL18)

Kittlitz’s Murrelet (AL20)

Crested Auklet (AL22)

Whiskered Auklet (AL26)

Four of these don’t fit because of the tarsus measurement Marbled Murrelet, Leach’s Storm-Petrel, Kittlitz’s Murrelet, Whiskered Auklet. Of the remaining three, only one has some white plumage (see that tuft between the two wings?) and an orange, upturned bill: Parakeet Auklet

Ruby South (WA) 10/10/14 found by Janis and Jody

Bill: 44 mm

Wing: 27 cm

Tarsus: 48 mm

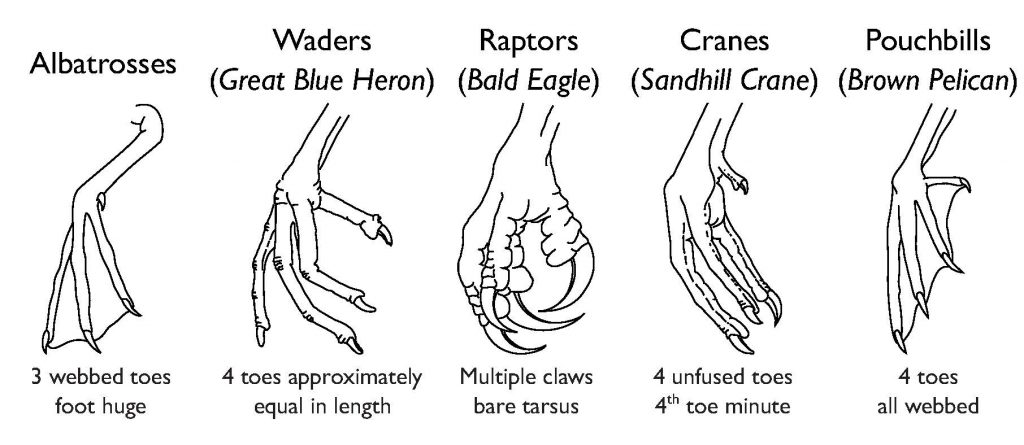

Alaska foot key (page 34), West Coast foot key (page 22):

Webbed (go to Q2), complete (go to Q3), 3 webbed toes 4th free (go to Q5), tarsus less than 1mm across (go to Q6), 4th toe has flap extending to tip of nail–Waterfowl: Diving Ducks.

Alaska: WF1: Bill with knob or feathers on sides: one of the scoters (WF5, WF9, WF7) or eiders (WF 21, 23, 27). Bill too large for any of the eiders except for the Common Eider. Wing too large for any of the scoters besides the White-winged Scoter. Between Common Eider and White-winged Scoter, measurements fit only one perfectly – dark plumage, white speculum and white eye patch – White-winged Scoter.

West Coast (2013): WF1: Bill with knob or feathers on top or sides – one of the three scoters, and only one has a wing chord that large: White-winged Scoter

West Coast (2002): WF1: White in wing! Feathers or knob on bill: White-winged Scoter or one of the eiders. Only the Common Eider is a contender, but its secondaries are dark (vs white in the White-winged Scoter).

Keith and Anita find a lot of interesting “large” debris at OR Mile 460. Although marine debris pilot COASSTers are not yet surveying for objects larger than 50cm, but these two couldn’t help but share several examples of “mortise and tenon” joinery, common to Japanese architecture but also used elsewhere and throughout history. This type of joint involves a mortise hole, several shown here, and a tenon tongue on an adjoining piece, that is inserted into the hole and glued, pinned or wedged in place.

Albert and Kathie went on their first marine debris survey on November 14th at Graysmarsh. They didn’t find any debris but did turn up an unusual find: an Ocean Sunfish, also known as Mola mola.

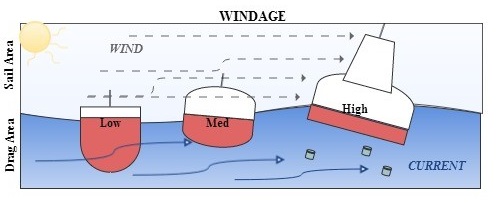

The Mola mola is the largest known bony fish in the world. An average adult individual typically weighs over 2,000 lbs, and they can reach up to 5.9 ft. in body length and 8.2 ft. fin to fin. Sunfish are most often found in temperate and tropical waters that are 50°F or warmer. They are often seen swimming on their sides, basking in the sun at the surface of the water to warm themselves after deep dives. Prolonged periods spent in water colder that 50°F can lead to disorientation and death for the sunfish, which most likely happened to this guy found in the Strait!

Seen something on the beach you’ve always wondered about? Send us a photo!

Cheers,

Erika, Julia, Jane, Hillary, Charlie, Heidi, Jenn, and the COASST Interns