Ever wondered what happens to the birds you tag on COASST surveys? And why do we tag them, anyway?

Much of the time, the carcasses are swept away with the next high tide, or are carried away by scavengers. Most times, a bird is never seen again. Think of all the others that are deposited once and for all on unsurveyed beaches – we are none the wiser!

Other times, we know exactly what happens to a beached bird. We have good evidence that they’re more mobile than you might think. In January, Bonnie Wood and Janet Wheeler at Salt Aire North found a Pacific Loon. Later that same day, Amy and Jack Douglas happened upon the very same bird on the neighboring beach, Bonge. Is that possible? Turns out, carcasses do move–by dogs, humans, or raptors. Without a unique tag combo, we’d never be able to trace such refinds.

Those dead birds untouched by animals and tides remain right where they are. Certain beaches are well known among COASST staff as “bird keepers.” These are often the most expansive sandy beaches, where a bird may be buried by blowing sand for many months, only to be uncovered and refound months later. The tags, then, are the only way to tell that such birds should not be counted as a “new” find.

We ask our volunteers to collect data on refinds each time they’re encountered. We don’t require measurements or photos after the original find, but we do ask for a few fields: where found, body parts, species, tie number and color sequence. Some volunteers do choose to take photos each time, and they allow us to make some fun “before-and-after” comparisons. In combination with refind data, this gives us an idea of which parts last– the feet and wings (the basis for the COASST guide).

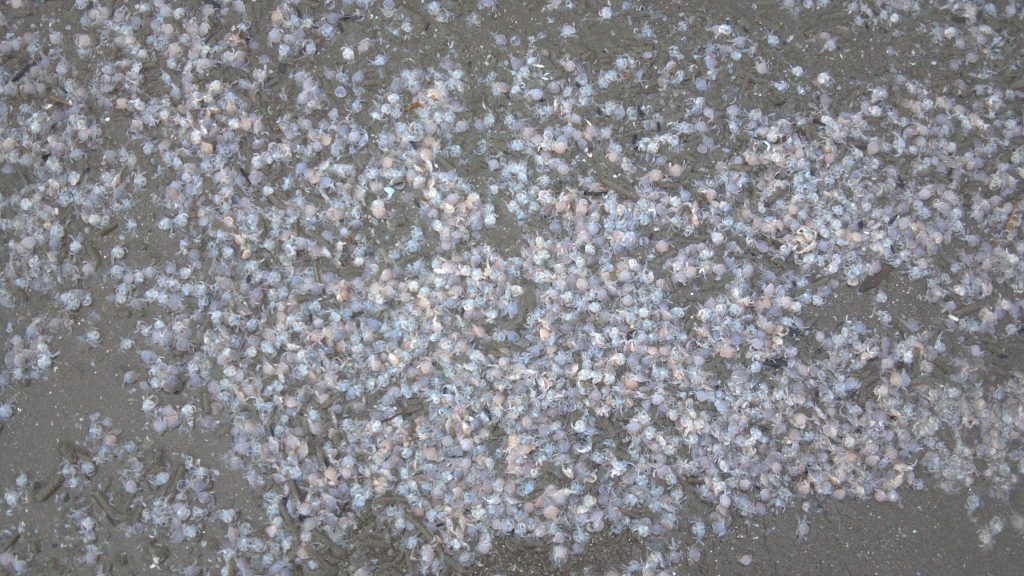

This intact Rhinoceros Auklet was reduced to just a sternum, the tagged wing bones, and a few other bones after 6 months on Agate Beach, in Oregon.

This Northern Fulmar was one of 24 found on December 3, 2010. A month later, it was found again, only slightly degraded. Then in September 2012, amazingly, it turned up again a whopping 21 months after its original find date!! A new persistence record for COASST!

All photos by Wendy Williams