It’s been a busy week at the COASST office, with juvenile common murre wreck reports in two Humboldt locations and lots of data coming in! If you happen to see 10 or more beached birds of the same species on your survey, check out Part 4 of the COASST Protocol and let us know if you have any questions about wrecks! We’re happy to help.

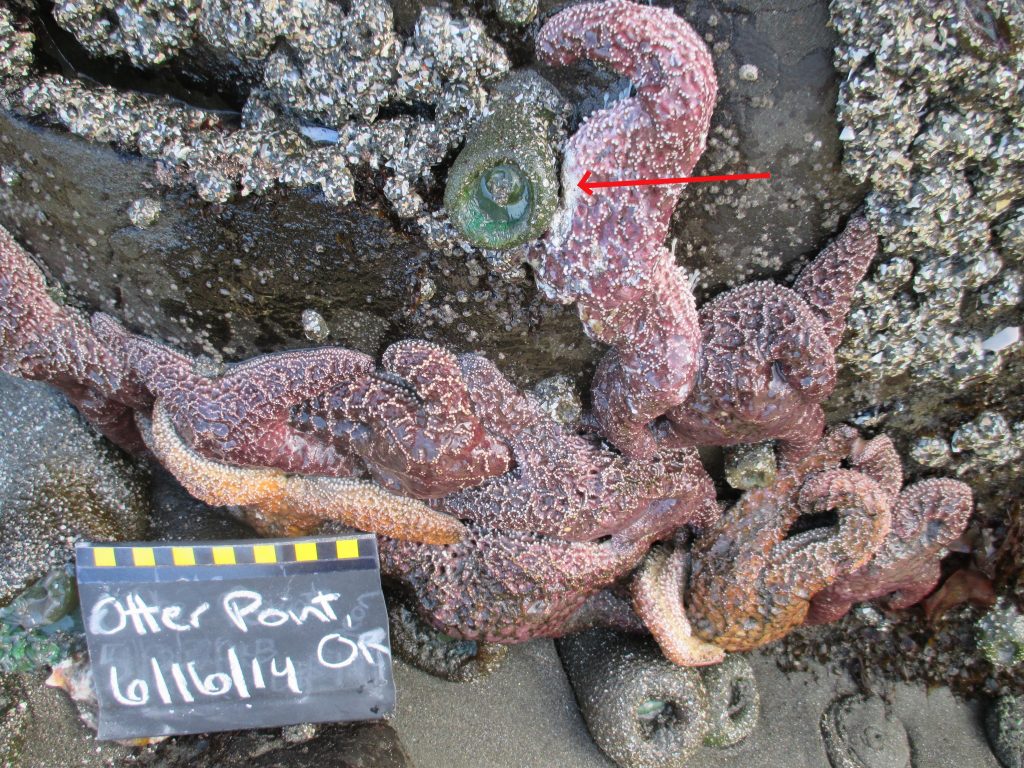

This weekend we have another low tide series, which means it’s a great time to head out for another sea star survey or your very first, if you haven’t tried the sea star protocol yet. More than 18 species of sea stars in the Pacific Northwest are exhibiting signs of Sea Star Wasting Disease, and we could really use your help to monitor sea stars on COASST beaches. Thank you again to those of you who have contributed thus far. There is no way we could monitor such a large geographic area without your help.

We’ve had quite a few interesting finds on COASST beaches recently, including what we call a one-in-a-million bird! What does that mean? Let’s take a look at what’s washed in and find out! We haven’t seen a flood of this species hit the beaches like what we saw in the summer of 2011 and 2012. Still, Brenda and Bill spotted one – only measurable part left is the tarsus. Let’s take a look, starting with the foot key (tarsus = 53mm): Webbed, go to Q2; completely webbed, go to Q3; 3-webbed, 4th minute (=tiny) go to Q6; thin toe or nail only go to Q7; heel is flat, go to Q8; with this tarsus, we’re at Tubenose: petrels – stop!

We haven’t seen a flood of this species hit the beaches like what we saw in the summer of 2011 and 2012. Still, Brenda and Bill spotted one – only measurable part left is the tarsus. Let’s take a look, starting with the foot key (tarsus = 53mm): Webbed, go to Q2; completely webbed, go to Q3; 3-webbed, 4th minute (=tiny) go to Q6; thin toe or nail only go to Q7; heel is flat, go to Q8; with this tarsus, we’re at Tubenose: petrels – stop!

On TN1, we can see that what’s left of the wings is larger than 20cm, so proceed to True Petrels. Bill is thin, long and dark – one of the shearwaters! With a 53mm tarsus, we’re outside the range of the Short-tailed Shearwater, and just barely in the range of the Pink-footed Shearwater. The PFSH has a pale bill base – well, Sooty Shearwater it is!

BJ and John found a one-in-a-million bird last week, not by species (we’ll get to that) – it was oiled AND entangled – only about a .002% chance of that! Let’s get back to what it is – crack open the foot key again: Webbed, go to Q2; completely webbed, go to Q3; 3-webbed, 4th minute (=tiny) go to Q6; thin toe or nail only go to Q7; but this time the heel is swollen: Larids – stop! Hooked bill, mottled brown plumage, dark bill: we have ourselves a Large Immature Gull, specifically a Glaucous-winged Gull, subadult.

Look at the size of that fish! Joanna didn’t find any birds on her Oregon Mile 309 survey, but she did spot this Yelloweye Rockfish (aka Rasphead, Red Snapper) on May 25. Yelloweye range from Prince William Sound, Alaska to Baja California, Mexico, though in the middle of their range, their population is low and declining, which led to a ban on their take in Washington since 2003. In 2010, they were listed as Threatened under the Endangered Species Act prompting a proposal of critical habitat in the greater Puget Sound/Georgia Basin in 2013 for Yelloweye, and two other species: Canary Rockfish, and Bocaccio. Yellow eyed rock fish can grow up to three feet in length. Yelloweye rock fish are red in color as juveniles and very slowly progress to a dull yellow. By very slowly, I really mean very slowly! These fish can live up to about 120 years!

Look at the size of that fish! Joanna didn’t find any birds on her Oregon Mile 309 survey, but she did spot this Yelloweye Rockfish (aka Rasphead, Red Snapper) on May 25. Yelloweye range from Prince William Sound, Alaska to Baja California, Mexico, though in the middle of their range, their population is low and declining, which led to a ban on their take in Washington since 2003. In 2010, they were listed as Threatened under the Endangered Species Act prompting a proposal of critical habitat in the greater Puget Sound/Georgia Basin in 2013 for Yelloweye, and two other species: Canary Rockfish, and Bocaccio. Yellow eyed rock fish can grow up to three feet in length. Yelloweye rock fish are red in color as juveniles and very slowly progress to a dull yellow. By very slowly, I really mean very slowly! These fish can live up to about 120 years!

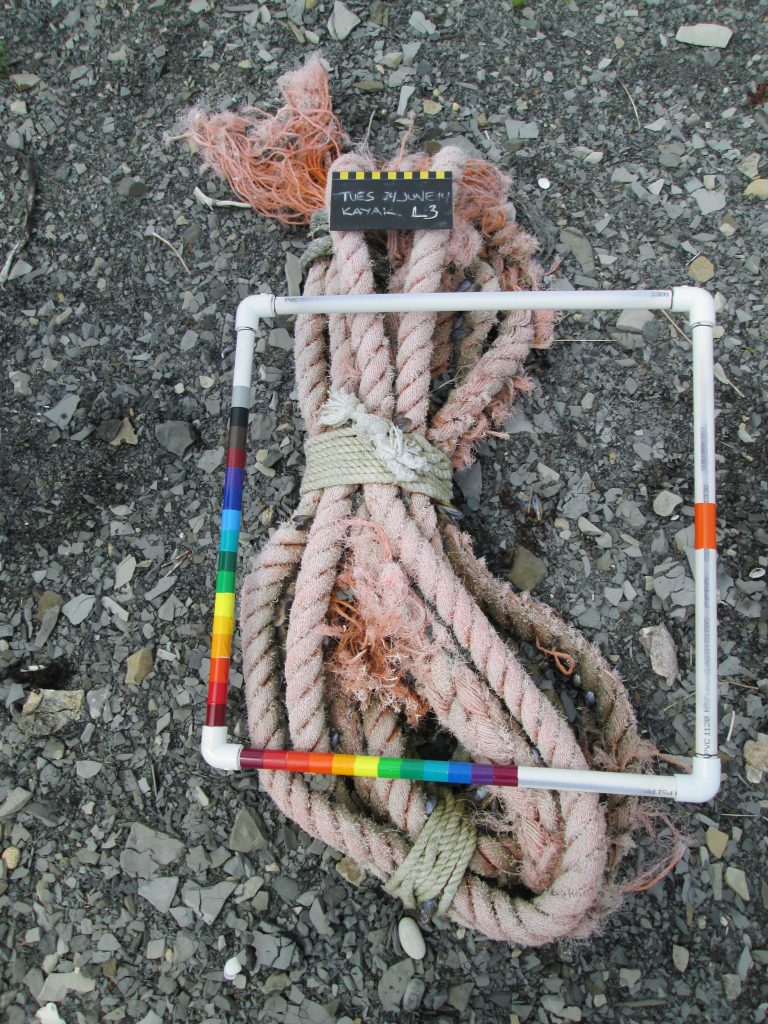

Wondering what’s happening with marine debris? COASST’s Executive Director, Julia Parrish, recently took a trip to Kayak Island, Alaska to test out the marine debris protocol. She was joined by Ellen Lance, Branch Chief for the Anchorage USFWS Endangered Species Program, and they found a lot of BIG debris. On the smaller side was this rope. A couple of key characteristics are the fact that it has many loops (a potential entanglement hazard for wildlife) and it has gooseneck barnacles on it (a sign that it has been in the water a long time and may have traveled a long distance). In this photo you can see our prototype measuring device/color bars used to determine the size and color of debris objects, along with the familiar COASST ruler and chalkboard.

Wondering what’s happening with marine debris? COASST’s Executive Director, Julia Parrish, recently took a trip to Kayak Island, Alaska to test out the marine debris protocol. She was joined by Ellen Lance, Branch Chief for the Anchorage USFWS Endangered Species Program, and they found a lot of BIG debris. On the smaller side was this rope. A couple of key characteristics are the fact that it has many loops (a potential entanglement hazard for wildlife) and it has gooseneck barnacles on it (a sign that it has been in the water a long time and may have traveled a long distance). In this photo you can see our prototype measuring device/color bars used to determine the size and color of debris objects, along with the familiar COASST ruler and chalkboard.

Thanks to all of you for your hard work! Happy COASSTing!

![6armssign[1]](https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/sites.uw.edu/dist/9/481/files/2014/03/6armssign1.jpg)