by Eric Wagner

Drive along Highway 101 down the Oregon coast to Lincoln County, and a little bit north of the city of Newport you will come to Agate Beach. The beach is an official state recreation site, and according to the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department, it gets a few more than 172,000 visitors each year. Those people can surf if they want, but razor clams are the main attraction. “Diggers, this park’s for you!” the state website proclaims.

For Wendy Williams,  that description doesn’t capture the full appeal of Agate Beach. “It’s basically a big sandy beach, but it’s pretty amazing for a lot of reasons,” she says. The beach is backed by a creek, which has a tendency to wander, its course meandering over the sand with the years. During the summer, when the northwest winds are steady, sand dunes will build up, some of them eight feet tall. “The place is just so dynamic and lively,” she says. “There are a lot of stories in the sands of Agate Beach.”

that description doesn’t capture the full appeal of Agate Beach. “It’s basically a big sandy beach, but it’s pretty amazing for a lot of reasons,” she says. The beach is backed by a creek, which has a tendency to wander, its course meandering over the sand with the years. During the summer, when the northwest winds are steady, sand dunes will build up, some of them eight feet tall. “The place is just so dynamic and lively,” she says. “There are a lot of stories in the sands of Agate Beach.”

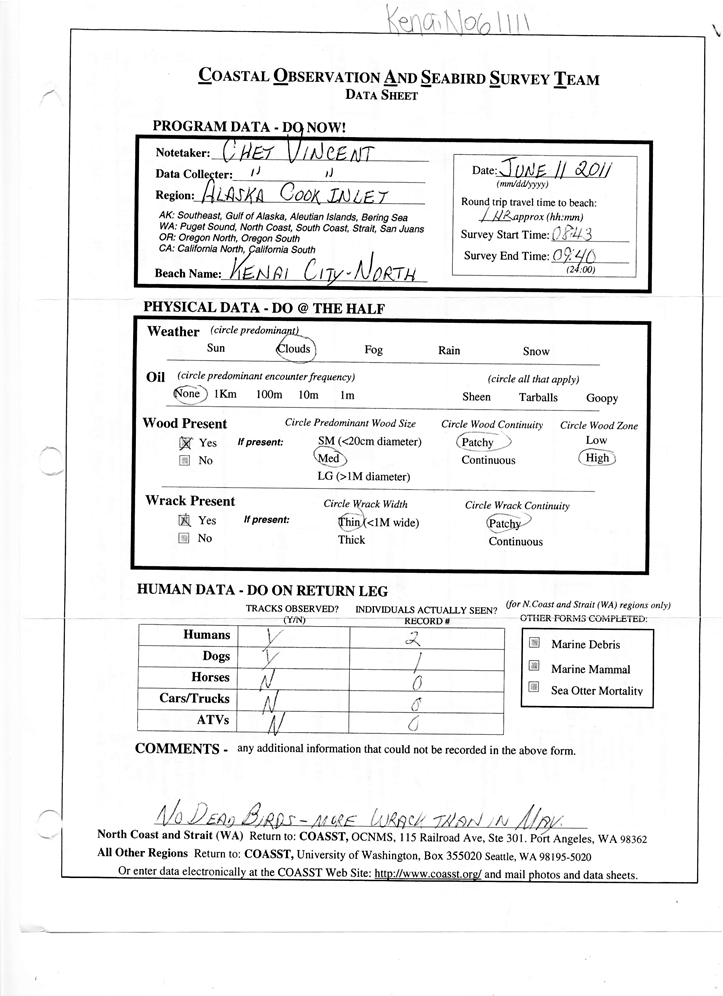

Williams knows her share of those stories because she has been walking the beach monthly since 2007 as a volunteer for COASST. In this, she has learned not only Agate’s particular rhythms, but also how they are linked with those of its influential surroundings. Sitting at the beach’s northern end is Yaquina Head, site of a well-known and well-studied murre colony. “I used to find lots of murres, until bald eagles and peregrine falcons started to cut down on fledging success,” she says, of the raptors’ return to the area. “But I’m still always bracing myself: how many chicks am I going to find come August or September because of death or nesting failure?”

Williams is more than passingly familiar with murres, in part from finding their bodies every so often, and in part from having earned a graduate degree from the Oregon Institute of Marine Biology in Coos Bay for her studies of their diving physiology. It was during her time at the OIMB that she learned to be a seabird observer, helping with aerial surveys along the coast and farther offshore. That work helped get her through school (both financially and spiritually, it sounds like), and also brought her in touch with the environmental consulting company with which she enjoyed a varied career as a seabird biologist. (Varied in more ways than one: “I ended up living in North Dakota for three years,” she says. “But I still called myself a seabird biologist!”)

Williams is more than passingly familiar with murres, in part from finding their bodies every so often, and in part from having earned a graduate degree from the Oregon Institute of Marine Biology in Coos Bay for her studies of their diving physiology. It was during her time at the OIMB that she learned to be a seabird observer, helping with aerial surveys along the coast and farther offshore. That work helped get her through school (both financially and spiritually, it sounds like), and also brought her in touch with the environmental consulting company with which she enjoyed a varied career as a seabird biologist. (Varied in more ways than one: “I ended up living in North Dakota for three years,” she says. “But I still called myself a seabird biologist!”)

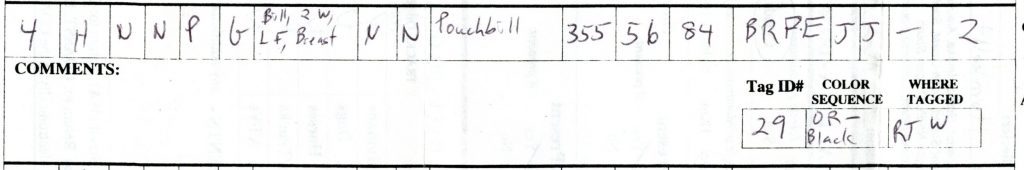

Any seabird biologist will tell you—even those outside of COASST—that dead birds are part of the trade, but Williams has taken that maxim to a certain extreme. She has worked on the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Prince William Sound in 1989, and the BP Deepwater Horizon blowout in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010, as well as several smaller scale oil spills. In all instances, Williams participated in the effort to understand what happened to birds once they died, so a spill’s fuller ecological cost could be better calculated. “Often with these spills, there’s chaos and everyone’s desperately trying to rescue and clean up the oiled birds,” she says. “However, the number of birds rescued or found dead doesn’t tell us what we really want to know, which is how many birds died from this spill event.” To address this question, she was involved in many projects on carcass persistence: radio-tagging seabird carcasses, distributing them widely, tracking the carcasses to see if they drifted to shore, and if so, documenting how long they lasted (i.e., were they scavenged, rewashed into the water, etc.).

“A lot of the questions we were  asking in Alaska and the Gulf were similar to the ones COASST is asking,” Williams says. “It shows why it’s so important to have background numbers in case of big mortality events.” And so in that way it makes sense that she started volunteering with COASST after she went to Agate Beach one day more than ten years ago and saw some dead birds marked with the ubiquitous COASST colored zip-ties. “We were just enjoying ourselves,” she says, “and there they were.” She contacted COASST and learned that the volunteer who had been responsible for Agate Beach was leaving. The beach was only about an hour from her home in Corvallis. “So I just picked it up,” she says.

asking in Alaska and the Gulf were similar to the ones COASST is asking,” Williams says. “It shows why it’s so important to have background numbers in case of big mortality events.” And so in that way it makes sense that she started volunteering with COASST after she went to Agate Beach one day more than ten years ago and saw some dead birds marked with the ubiquitous COASST colored zip-ties. “We were just enjoying ourselves,” she says, “and there they were.” She contacted COASST and learned that the volunteer who had been responsible for Agate Beach was leaving. The beach was only about an hour from her home in Corvallis. “So I just picked it up,” she says.

At the same time, and considering the breadth of her experiences with dead birds in some of their more soul-wringing circumstances, it might seem a little odd that in her spare time Williams would choose to watch for more dead birds, spending as much as five hours at a time meticulously searching for them. But that is not the case at all. “Whatever has happened in my life, no matter how intense some of the projects have been, I have always enjoyed having this work to do,” she says. COASST gets her outside, and she feels like she’s making a contribution, and that’s something she’ll always love. “I would go out to Agate Beach two or three times a month if I could,” she says.