What do COASST staff do on their time off? Walk the beaches, of course!

And it was on such an excursion that Charlie Wright, the COASST verifier, and his wife Linnaea – both expert birders and natural historians – happened upon a Blainville’s beaked whale.

A what?!?

Beaked whales are one of the oldest and most speciose lineages of cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoises), with 22 species documented to date. Smaller than the large whales, and sometimes mistaken for dolphins, beaked whales have, as the name implies, a dolphin-like “beak” (or rostrum). Vaguely sausage-shaped, they also sport short stubby flippers (front limbs), a small dorsal (back) fin, and a plain un-notched tail (also known as a fluke). Males have two enormous teeth that look more like spade-shaped tusks, which they apparently use to fight other males for access to females. These teeth vary by species and allow easy identification of males. With no teeth to examine, the whale Charlie and Linnaea happened upon was a female.

Relatively unseen and unknown animals that range widely across the world’s oceans, beaked whales are deep divers that can submerge in the hunt for squid and deep-sea fish for over an hour. No wonder people don’t often see them. But they do wash ashore. In fact, in 2014 a previously unknown species of beaked whale washed up on Zapadni Beach on St. George, Pribilof Islands (a COASST beach!).

All of the excitement over this rare find got us wondering, what kinds of marine mammals have COASSTers been recording over the years? Although COASST doesn’t “officially” collect marine mammal data, since 1999 COASSTers have often reported what they find. From 2000 through the present, just over 1,200 marine mammals were reported, most to group, like “seal” or “dolphin/porpoise.” Just over half (644) were identified to species. In our new COASST protocol, we’ve added specifics about how to record and take photos of any beached marine mammal observed.

What can we say about these data?

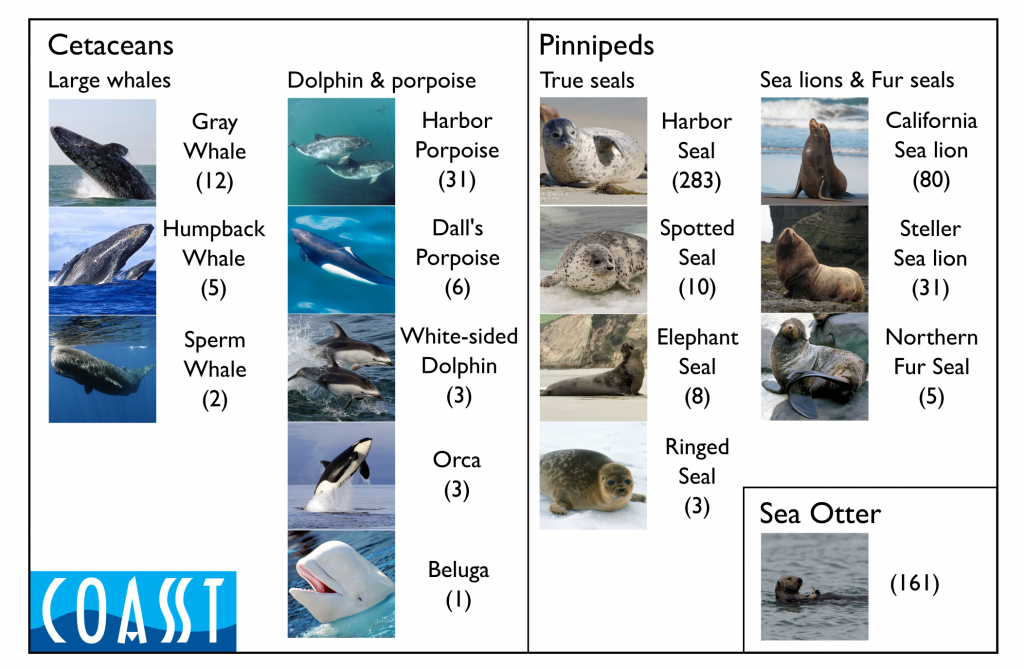

First, we focused on the marine mammal carcasses identified to species. These data are presented with numbers in parentheses under each photograph indicating the total count. The winner? Harbor seals, followed by sea otters and California sea lions. Not a single beaked whale! Notice that although there are slightly more species of cetaceans (8 in total compared to 7 pinnipeds), COASSTers are far more likely to find a pinniped (420 individuals versus only 63 for cetaceans).

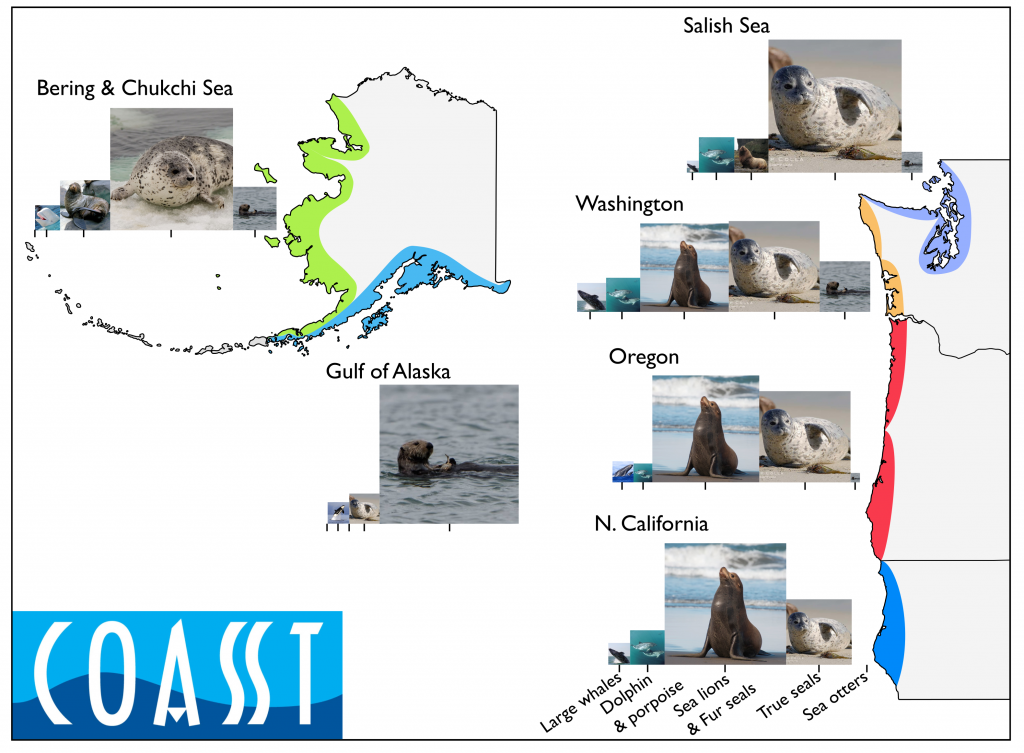

Second, we mapped all of the species groups, from large whales to sea otters, as a function of location, from northern California north to the Bering and Chukchi Seas. The “image collage” adjacent to each mega-region (we’ve combined the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Puget Sound and the San Juan Islands into “Salish Sea”) shows which species groups are found where. The size of the photograph is proportional – bigger photos literally mean more of that group is found, and the image indicates which species in the group was identified most often.

In California, the group “sea lions and fur seals” dominate, with the vast majority of identified finds being California (of course!) sea lions. North in Oregon and coastal Washington, “true seals” become more abundant in the finds identified to species. In the Salish Sea, as many COASSTers can attest, harbor seals dwarf all other marine mammal finds. In fact, the chance of finding a harbor seal is not that much different from the chance of finding a beached bird (the recent Rhinoceros Auklet mortality event being an exception).

Sea otters, unknown from our California beaches and a true rarity along Oregon, become relatively more abundant along the Washington outer coast, and dominate the Gulf of Alaska beaches.

And then there are the finds in the Bering and Chukchi Seas. Notice that the only photograph in common with the other COASST mega-regions is the sea otter, everything else is different. “True seals” dominate, but the species isn’t harbor, it’s spotted. Rather than sea lions, COASSTers in these regions are more likely to find fur seals. Not surprising when you consider that the Pribilof Islands (home to 8 COASST beaches) support breeding rookeries of Northern fur seals numbering in the hundreds of thousands.

Documenting beached marine mammals is an important objective for COASST. So keep an eye out for the odd flipper, fluke or paw as you’re searching the beach. With marine mammal populations shifting in abundance throughout the COASST range, we’re in the perfect position to create the definitive baseline.