We hope you are all raising your glasses tonight in celebration of Julia and the COASST program receiving the White House Champions of Change award on Tuesday, June 25. You can read Julia’s blog about how it takes a village to make citizen science a success, or for those of you that missed the 6am(!) live stream from Washington DC, you can watch the event on You Tube (Julia begins at approximately 11:00 of the 1:26 video). And if you just want to read it, well, you can do that too:

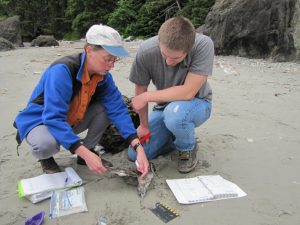

“COASST started in 1998 with 12 volunteers in Ocean Shores, Washington. Those 12 people were going out on the beach monthly to literally pick up dead birds, figure out what species they were, and report that back to me at the University of Washington.

Now over 15 years later, COASST has 850 people walking the beaches from Eureka, California north to Kotzebue, Alaska and west to the Commander Islands (which are in Russia, right a the end of the Aleutian Island chain). COASST has identified 160 species and has found over 30,000 carcasses identified to species (pretty, geeky, I realize). We’ve used that data to figure what’s going on with fishery bycatch, to document harmful algal blooms, to look at Avian Influenza, to look at the effects of climate warming, and to look at historic use of seabirds by Native Americans as food sources.

COASST is Kathleen Wolgemuth, an 80-year old from Ocean Shores, now battling cancer, still out on the beach every month with her daughter Beth.

COASST is Robert “Olli” Ollikainen from Tillamook, Oregon. An avid Huskies fan (and I hope he’s watching), has literally scooped up the whole town to volunteer with him. And actually made a dead bird float in the 4th of July parade. [laughter]

COASST is Olivia Vitale age 15, started at age 12, surveys with her dad, Don, on Bainbridge Island. And put her first bird find on You Tube.

COASSST is Daniel Ravenel from Taholah, Washington, who works for the Quinault Tribal Nation Department of Natural Resources. Surveys with his dog, Denali when he’s not in the Coast Guard Reserves, coming from a military family.

And what brings those people together? It’s not their age or their race or their ethnicity. It’s not their politics or their education level. It’s not their job or their gender. It’s that they have a very, very strong sense of place. They love their place. They want to know about it. They worry about it. And by participating in citizen science, in rigorous citizen science, they know they can gather the data, they can work with scientists, and together we can make a difference. Because only with that very broad extent, fine grain data, can we solve the environmental problems that face us today.

So science is important. But people are important too. And the world is changing very fast. There are just too many issues and problems for scientists to deal with alone. So we need an army and we need a village.

Last century was the century of “Ivory Tower science,” where you had to have a PhD to be a scientist. But this century, is the century of citizen science. Where everybody – everybody in this room, everybody who’s watching, everybody in the country, everybody in the world – can be part of a science team and make a difference.”