In 2013, COASST got its first grant to expand to a whole new data collection protocol – marine debris. Following the tsunami of 2011 that resulted from the Tōhoku earthquake, this was a no brainer. But debris had been on the minds of many COASSTers well before the flotsam from Japan hit our coastlines. In fact, many COASSTers have always gone to the beach armed with a trash bag.

It’s definitely a nuisance, and can also be a health hazard for humans and wildlife alike, but could it also be science?

Could regular monitoring uncover patterns of trash on our beaches?

That’s what Hillary Burgess, the COASST Science Coordinator was brought on to figure out. And after years of development, input from more than 75 pilot testers, 30 interns, marine debris experts and the COASST staff and Advisory Board, we’ve not only got a viable program, we’re starting to “see” the patterns.

This is the first blog in a series revealing what Marine Debris COASSTers are finding. Not quite (!) as numerous as COASST Beached Birds, and certainly not as long in the tooth…, our marine debris program is off to a fantastic start. As of mid-November here are the numbers:

- 110 unique beaches surveyed

- 341 small debris surveys

- 432 medium debris surveys

- 403 large debris surveys

- 185 participants

- 13,396 items characterized

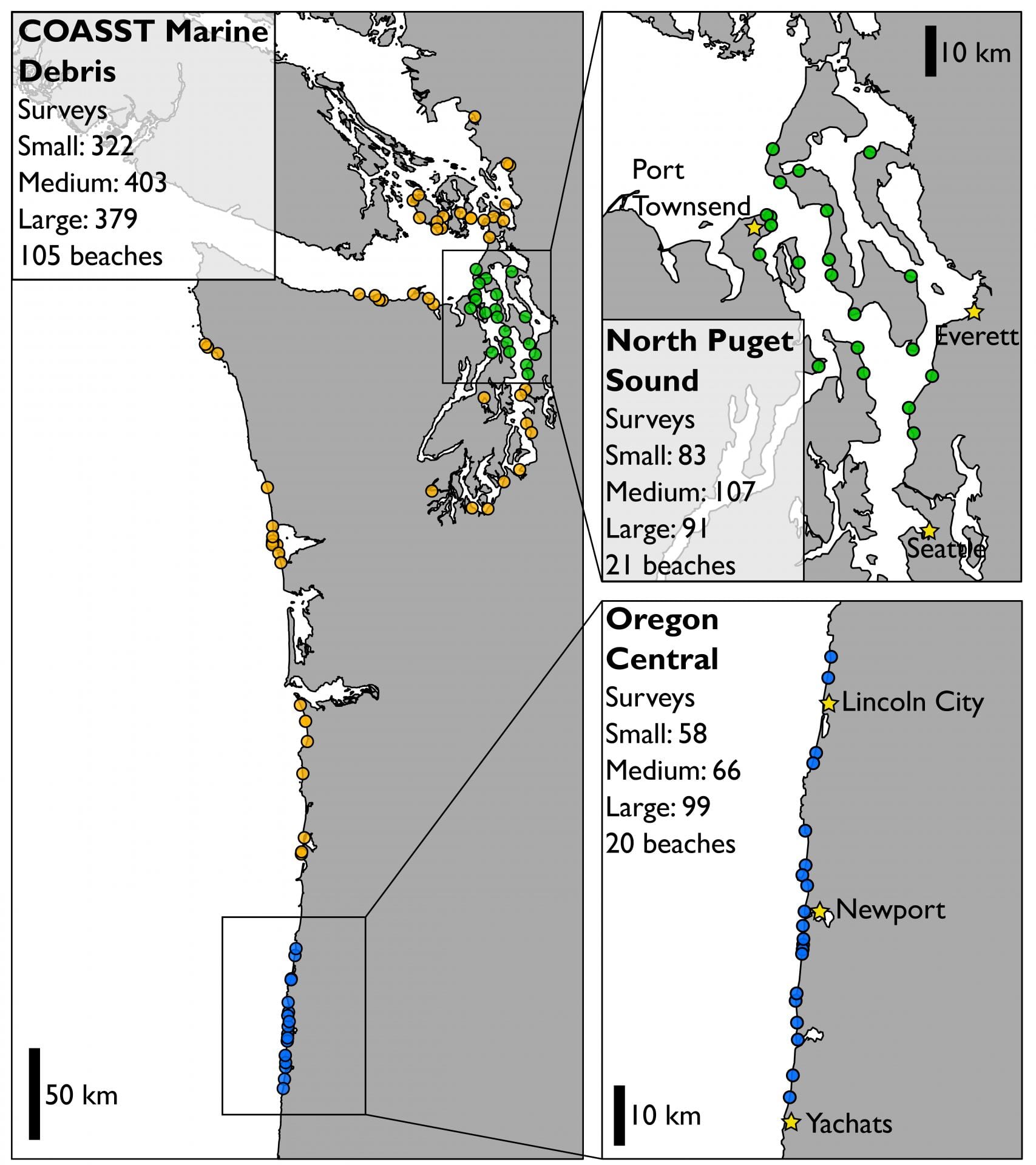

COASST marine debris survey sites have been monitored most consistently for the longest time in North Puget Sound and Central Oregon.

Although COASST marine debris data comes from throughout Washington and Oregon, and even a few test sites in Alaska, we’re confining our analysis for the moment to two regions with a multi-year, multi-beach sample size, and some pretty interesting differences: the outer coast beaches of Central Oregon, and the protected waters of North Puget Sound.

First, let’s step back to some basics. When considering how many beached birds COASSTers find, we use a measure we call “encounter rate” or the number of carcasses a COASSTer might find per kilometer of beach surveyed. Encounter rate treats all beaches – wide ones and narrow ones – the same. And when COASSTers search for carcasses, they comb the entire beach – from the waterline to the vegetation.

Debris is different.

First, we separate debris into size classes:

- Small Debris (<2.5 cm; think cigarette butt, bottle cap and smaller)

- Large Debris (>50 cm; think lumber, large pieces of Styrofoam, tires, fishery gear)

- Medium Debris (all the stuff in-between, or 2.5 cm to 50 cm; think cans, bottles, rope pieces and bags)

Second, we report the amount of debris as a function of the area searched. So, not per kilometer, but per 10,000 meters squared (10,000m2), or 100m2 to ensure that the values we present are meaningful. To put these areas into perspective, 10,000m2 is approximately the area of two football fields and 100m2 is one quarter the size of a basketball court.

Third, we take account of the differences in the amount of debris in five (5) different beach zones:

- Surf – waterline to the lowest, freshest line of wrack

- Wrack – lowest, freshest line up to the oldest line laid down by the monthly tidal cycle

- Bare – any bare substrate (sand, cobble, whatever) above the wrack zone

- Wood – the backbeach where driftwood accumulates

- Vegetation – where the live vegetation takes over

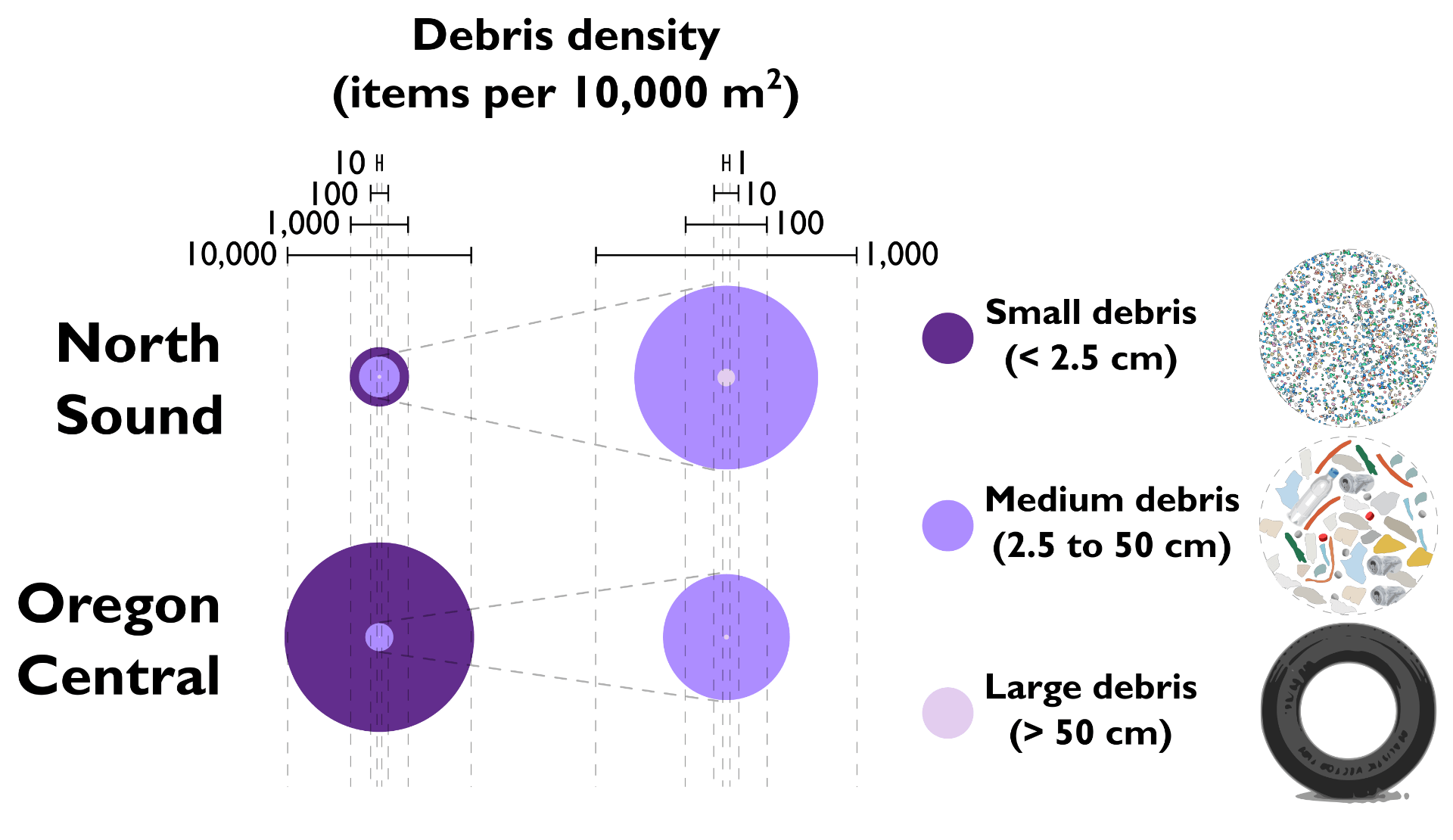

Not surprisingly, small debris – the count of small debris (per 10,000m2) is much higher than that of medium debris, which is more numerous than large debris. And this pattern holds for the outer coast, and for Puget Sound. However, there is a lot more small debris on the outer coast!

The bubbles on the left illustrate debris density, or the estimated count of pieces – by size – you might find on average – from the waterline to the vegetation, scaled to 10,000m2. Small debris (darkest purple) is very abundant, and especially in Central Oregon, where you could find upwards of 10,000 pieces in a 100 meter by 100 meter area of beach! In the middle is a blow-up of the medium and large debris pattern (because those numbers are dwarfed by small debris we had to separate them out and blow them up). To the right is the color code, and a schematic of the relative sizes and types.

And the reverse is true of medium debris – inside waters have a higher density than beaches along the outer coast. The pattern is similar, albeit less pronounced, for large debris.

Where is all of that small debris? Mostly in the wrack, at least in Central Oregon. Conversely, along these outside waters beaches, medium and large debris are primarily found in the vegetation, and secondarily in the wood zone. (Note that small debris are only sampled in the wrack, bare and wood zones).

North Puget Sound COASSTers find similarities, and differences. Small debris is also most numerous in the wrack zone, but the wood zone has just under 90% of that peak density, and the bare zone sports just under half of peak density. Medium and large debris are primarily found in the wood zone, but density in the vegetation falls off quickly, in contrast to the vegetation zone on outer coast beaches.

We’ll compare a kilometer long “typical” beach in North Puget Sound to one along the coast of Central Oregon averaged over the year. You would be lucky to find a single bird in your North Puget Sound beach survey, but you’d likely find 5-10 large pieces of debris, 1,000 medium pieces, and a whopping 2,500 small pieces.

Seems like a lot, until you travel to the coast of Oregon. Here you would find on 3-5 birds averaged over the year, 3-4 large pieces of debris, 2,500 medium pieces, and a stupendous 100,000 pieces of small debris.

The humongous medium and especially small debris numbers are why COASST subsamples the beach. Otherwise, Sisyphus would long since have been successful in rolling his rock up the hill before any outercoast COASSTer finished picking up all of the small debris! A somber note, of course, is that this is what we face along our beaches and in our ocean, and – you guessed it – it’s almost all plastic, with 70% of medium debris and 87% of small debris items being plastic.

Reply below or email coasst@uw.edu with your guesses and suspicions. Thank you as always for sharing your expertise!

Reply below or email coasst@uw.edu with your guesses and suspicions. Thank you as always for sharing your expertise!