by Eric Wagner

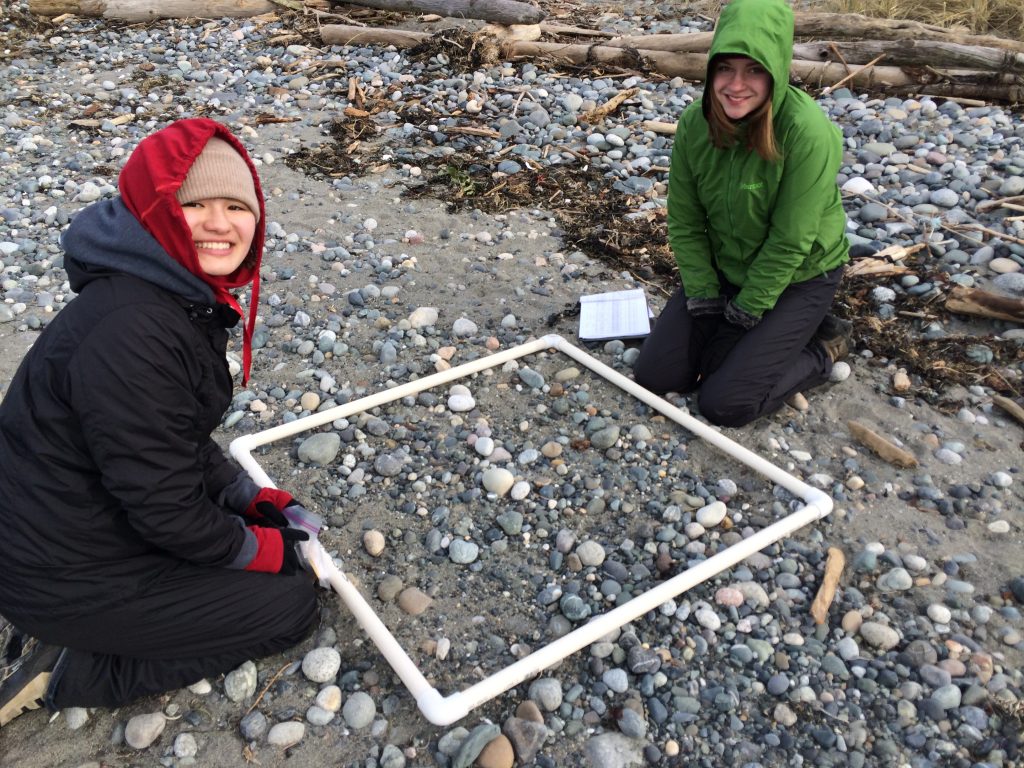

Allison DeKerlegand helps with the marine debris side of things. She studies environmental science and resource management, and did a study abroad in Australia, in North Queensland, near Cape Tribulation. Apparently its name is apt. “The beaches there have just as much debris as our local beaches,” she says.

Maddy Hoiland took a course in environmental studies and liked it, but she wanted to apply the things she was learning in it in the real world. She emailed Jackie Lindsey last spring, and has since helped with data entry and mailings.

Jess Quinn is a second-year student in the School of Aquatic and Fisheries Sciences. Her roommate was a COASST intern before she was, which was how she learned more about the program. She has what she describes as a “whiteboard enthusiasm” for population genetics research, but she also feels it is important to see and understand the natural world. (Not that these impulses are mutually exclusive, of course.)

These are just a few of the current crop of COASST interns who help to keep the program humming. Interns are vital to the COASST enterprise, and COASST has had over 250 since it began almost twenty years ago.

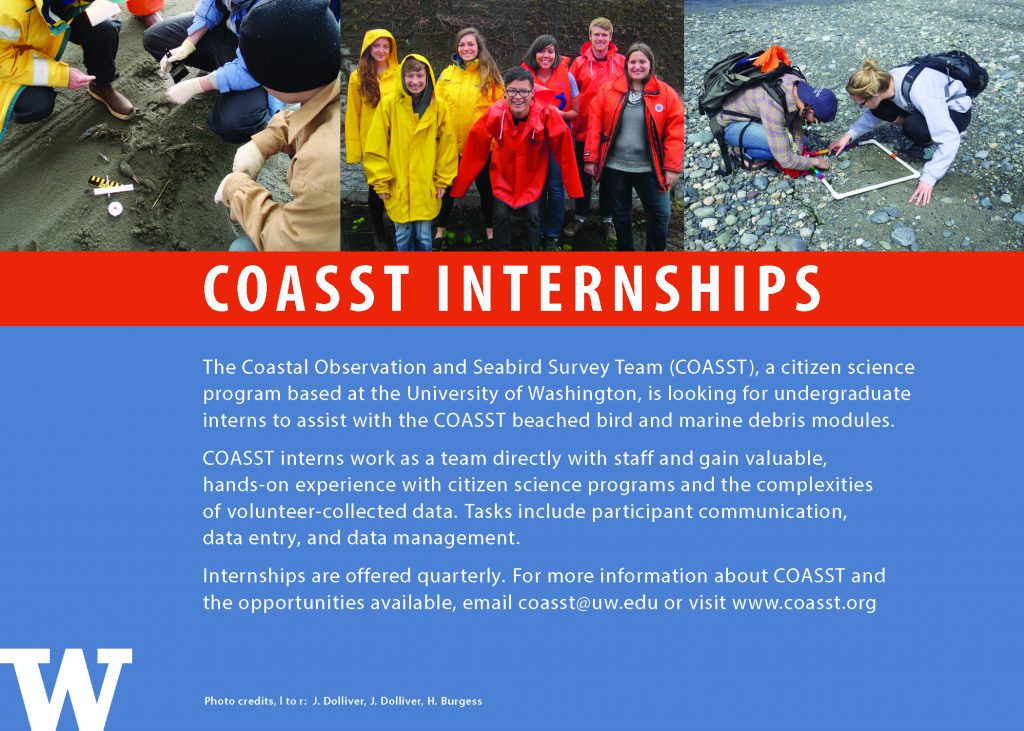

Left to right: Andrew, Andrew, Emily, Bailey, Tim, Jane, Justin, Abby. (COASST dog Freya, front and center). 2018 COASST intern field trip 2018.

Nowadays, all student interns start out in COASST as generalists, helping with data and participant questions, and crafting survey materials. They learn about every piece of the program, and begin to see how those parts come together as a whole. After a quarter or two they begin to focus more on their favorite aspects of COASST. Some stay with data entry, or help put together survey kits, and others lead outreach and email projects.

In the first quarter of their internship, students will spend about eight hours per week in the COASST office learning the ropes, but after that the commitment can be more flexible. “COASST couldn’t run without our interns, so it’s great for us,” says Jackie Lindsey, the Participant Coordinator. “And the students learn a lot, too, about data management and processing, about communicating science and engaging the public.”

Even if they do not stay in citizen science, former interns have found their COASST experience can help in unexpected ways. Chris Biggs, for example, was an intern about nine years ago. “Interning with COASST just sounded like an interesting opportunity that was different from a lot of the other internships that were available at the time,” he remembers. “I didn’t know much about citizen science, but was intrigued by it, and I thought I could learn more that way.”

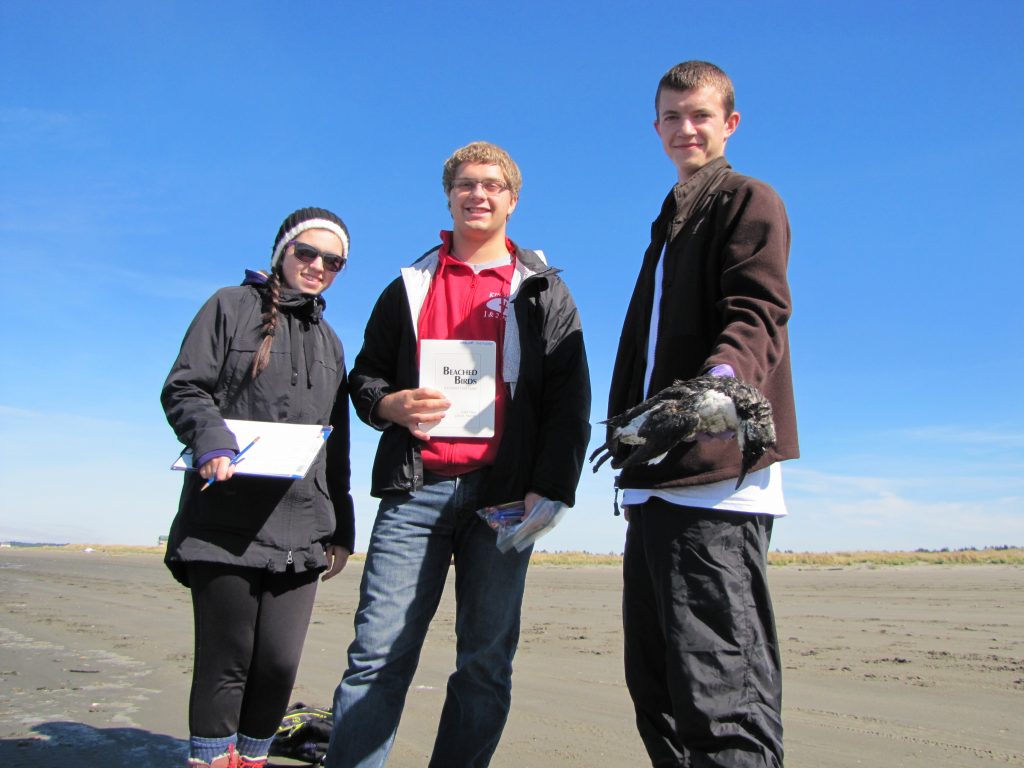

Learn he did. Biggs helped with data entry from the seabirds surveys, he did some work on seabird ID quizzes, he represented COASST at the annual shorebird festival at Grays Harbor. “It was a lot of fun,” he says. He is now at the University of Texas at Austin, finishing his Ph.D. in fisheries ecology. (You might have heard of him—he is New York Times-famous.)

Chris Biggs conducting research on seatrout for his graduate program at the University of Texas at Austin.

Although his work has nothing to do with seabirds or marine debris—he studies fish spawning—Biggs says the experience definitely helped in other ways. Part of his research has him interacting with local recreational fishers, so he can get information on the reproductive status of the fish they are catching. “I learned a lot about working with the public and non-scientists,” he says. “These days, it’s important for scientists to know how to talk to people who might be interested in what you do but are not necessarily trained in that field. So yeah, in that way it was a big help.”